Szabolcs Morvay - László Ponyi: The role of community culture and agoras in creative cities

Cikk letöltése: pdf2021-06-01

Abstract: Creative cities have been developing in the post-industrial era and in post-industrial societies. In fact, we are talking about a direction of urban development in which culture and creativity are potential resources for building successful and competitive cities. Culture feeds our spirit and builds our communities, and creativity helps us to find new answers, new paths, new solutions, new “colors”, that is, new content. It is clear, the concept of the creative city emerges as a direction of urban development that places greater emphasis on human capital, communities, and culture than the cities of industry and commerce. In the process of this city-evolution, public education, cultural provision - within the cultural field – has a primary role, because it has organizational, operational, insfrastructural and human resources background, which are essential conditions and pillars for various cultural activities, basic public cultural services and the creation of communities. It is an exciting question to discuss the role of Hungarian public education, its institutional system, methodologies and programs in the flow of unstoppable urban development processes, as this role can help cities to reborn in the future as settlements where culture flourishes and communities are strengthened.

Introduction: Post-industrial society and culture-based urban development

The post-industrial era or post-industrial society first developed in Western societiesThis social transformation can be explained not only by technological changes, but primarily by changes in consumer behavior. The development of a consumer-oriented society was accompanied by the expansion and extension of the cultural sector. Global processes replaced Fordist mass production with the post-Fordist economy, the investment in physical capital, the economy based on raw materials no longer fully contributed to the competitiveness of the countries, research and development, innovations, creativity, and placing a higher value on human capital became the engine of development. We can observe the rapid development of the new trend in the western, developed countries, with the increasingly significant growth of the creative economy and cultural economy. In particular, Western European and North American regions tried to compensate for degraded industrial sectors with cultural investments and the establishment of research centers. Examples include Birmingham's educational and cultural complexes, Pittsburgh's cultural institutions, or the Ruhr region. (Enyedi 2005, Florida 2002)

In addition, the transformation in question can also be seen in the policy of the governments, because instead of the passive executive state policy an active public service policy began to take place,, a policy that promotes local development. So much so that the so-called the development of creative cities has become part of a strategy to attract investors and highly educated, highly qualified professionals, which Richard Florida referred to as the creative class. (Florida 2002)

This strategy included the implementation of an elitist policy that supported the so-called gentrification. In this strategy, the revitalization of cities began, based on broad architectural projects and cultural institutions. (Bianchini 1993) Spectacular events began to enrich the cultural life of the cities, and the development of creative and cultural industrial clusters began. The process triggered the creation of modern infrastructure. The dynamic local milieu facilitated the development of a wide range of entertainment options, restaurants and nightlife. (Ulldemolins 2014)

The cultural strategies generated in the crossfire of these processes initially focused on boosting tourism and consumption, and they tried to improve the townscape and image by creating large, iconic cultural projects, art districts, and entertainment venues. From the 1990s onwards, the role of human capital and innovation in urban growth was increasingly recognized, at the same time, political discourses turned towards the traditionally separate sectors of art and media activities. (Flew 2012)

So the rise of the cultural and creative industries, the unfolding of cultural life, as well as the cultural aspirations of cities are the products of the post-industrial age, as a consequence of which we can speak of the rise of the so-called cultural or creative cities.

In order to explore the Hungarian context of urban development, we must mention the studies of Viktória Szirmai, an urban researcher, who studied the Hungarian urban areas and their social structure. The analyzes pointed out the inequalities that characterize the Hungarian spatial structure based on infrastructural and institutional provision. These inequalities include the concentration of the higher-status social strata in settlements higher in the settlement hierarchy. In fact, we can speak of a spatial social hierarchy, where the concentration of highly qualified labor can be observed, who can actually be identified with Richard Florida's creative class. In the Hungarian urban areas, the so-called the center-periphery model prevails, in which the hierarchical character of the spatial social structure can be observed moving from the center to the periphery. The center-periphery relationship includes economic, infrastructural and institutional supply differences, which can also be characterized by the so-called a social slope. At the same time, this social slope is flexible, the trend of decreasing social status value changes along the settlement hierarchy as a result of suburbanization. (Szirmai 2007)

In fact, we can count the development of creative cities as an urban development process of "good direction", behind which cultural strategies and conscious urban policy efforts are working. Where do community culture and its institutional system appear in these strategies? In order to get an answer to this question, the nature of creative cities will be outlined below, as well as the analysis of the extensive and diverse institutional system of community culture, so that we could highlight the common points, the conscious grasping and connection of which can generate synergy effects in promoting progress on a path that moves towards a common goal: towards the development of culturally rich, creative and diverse settlements that are home to communities.

The creative cities

The creative city as a concept is based on two things. On the one hand, on culture, which feeds our souls and builds our communities, and on the other hand, on creativity, which provides help in the search for new answers, new ways, new solutions, new "colors", i.e. new content. If society builds on culture and creativity, it can generate high levels of economic value and social well-being. As a result, culture and creativity are increasingly being directed towards the center of European decision-making, but at least they are receiving more and more attention. Elements such as the promotion of cultural diversity, the protection of cultural heritage, the support of cultural and creative industries, and, not surprisingly, the creation of jobs and the enhancement of economic growth (The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor Edition, 2017) are in focus.

Exploiting culture and creativity as potential resources has recently entered the urban context, becoming a dominant source of successful and competitive cities and regions. Several creative city models have been created, but the most dominant is Richard Florida's model, which fundamentally influences contemporary cultural policies. The Florida model is a city and regional development concept built around the concepts of work, place and creativity. It emphasizes the contribution of cultural services and creative professionals to urban and regional identity and livability, as well as the need for creativity for successful and globally competitive post-industrial cities and regions (Tara 2012).

Creative city was earlier mentioned in the 1980s, however, it was only in the 1990s and 2000s that this concept became permanently used. Originally, cultural policies were tools of attempts to stop the decline of post-industrial cities, and after the recession of the 1970s, interest in the role of culture in economic growth increased (Bianchini 1993). Charles Landry, in his work entitled "The creative city", defines a culture-oriented theory, that is, he interprets the creative city as a settlement whose primary sources and basis of value are cultural resources, which take the place of coal, steel and gold. At the same time, Florida sees the creative city as a city that can attract highly educated people and creative professionals. What is common between the two trends is that Florida believes that the cultural values of cities are attractive to talented people, knowledge-based workers - the creative class (Landry 2000, Florida 2005). In addition, it should be emphasized that the creative city uses creativity as a key element in the social, environmental and economic issues of the city. The creative city concept is popular in local government circles and is connected to the framework of the knowledge economy, including the concepts of innovation, growth, entrepreneurship, and competition (Galloway and Dunlop 2007).

Nevertheless, the practice shows an ambivalent picture, that is, the way cities implement the idea or concept of the creative city in practice. In adapting the concept, many cities only create a good slogan with which they want to reposition and define themselves. In these cases what is missing behind the slogan is a comprehensive urban development concept that relies on cultural and creative resources. Several cities developed creative city strategies, which were mostly economy-oriented, which means that they contained interventions focusing economic development ideas exclusively. As an example, we can mention the big Dutch cities - Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Utrecht - which aimed to directly support creative enterprises and establish a creative business climate, but the soft factors of the creative city - culture, social aspects, tolerance - were pushed into the background (Kooijman and Romein 2007). On the other han, we can talk about "convinctive" creative cities, which declare themselves to be absolutely creative cities. One study from 2010 mentions 60 self-proclaimed creative cities worldwide. (Karvounis 2010) There are cities that we would generally consider less creative cities, yet they have started to redefine themselves as such, for instance Sudbury in Canada, Milwaukee in the United States, Huddersfield in the United Kingdom or even Darwin in Australia. In addition, the number of scientific works on the topic of the creative city has also increased. From 1990 to 2005, the number of references to the term creative city was moderate, the annual citations were below 200, while from 2005 it increased rapidly, and from 2010 the number of annual references rose to over 800. (Scott 2014)

After all, the creative city concept offers a tempting vision for cities. It conveys the message that creativity is a key element in achieving urban development goals. Nevertheless, it is a fact that cities have always been the hub of creativity. (Andersson 2011) Today, urban creativity is integrated into a new cognitive and cultural system from the existing socio-economic relations. Creative city policies also accelerate gentrification processes, which entails the exclusion of lower-income families from downtown areas. (Andersson 2011) Although the creative city theory puts a lot of emphasis on diversity, tolerance, and political support, we can actually see only a few gestures towards social inclusion and even less towards a fairer redistribution of income. Furthermore, as a result of the creative city discourse, cities often launch flawed programs in the hope that these investments will attract creatives, leading to an increase in urban prosperity. However, in several cases it turned out that the expenditure of investments far exceeded the expected return on investment, as the decision-makers had too much hope referring to models such as the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao. (Scott 2014)

We are right in asking how to measure the creativity of a city in any way. What elements should the city decision-makers deal with if they want to strengthen the creative character of the settlement? What does it actually mean that a city is creative? What indicators can be used to express the level of creativity of a city? Apart from researchers, international organizations, and the institutions of the European Union as well have been dealing with these questions for more than two decades now. Back in the 1970s, it was clear that some answer had to be given to the urban problems of declining industrial centers, and therefore urban studies tried to include a new element in their analyses, which was actually culture, later creativity, and the creative economy. In the last decade, creative individuals have also come into focus, their embeddedness in the urban environment, as well as the openness of the city, the exploration of opportunities for connections with urban economic policy, and support policy to alleviate the vulnerability of creative actors in the labor market, the creativity-based shaping of the urban vision of young people, as well as, promoting the exploitation of creativity as a potential ability. (Tokatli 2011, Pratt 2011, Allen and Hollingworth 2013)

From the elements and mosaics mentioned above, the ideal image of a creative city can be assembled: a city where the creative class is strongly present, the city policy provides them with a supportive environment, creativity and art education play an important role in the education and training of youngsters, cultural investments, developments shape the cultural facilities and cultural life of the city and the its economy includes businesses that can be linked to the creative sector.

At the same time, it is worth structuring the set of creative cities made up of individual elements, since different tools and approaches are needed to foster their strengthening. In this way, we can talk about the culture-oriented interpretation of the creative city, which basically gives priority to the creative and cultural activities taking place in the city, and stimulates the emotional and spiritual quality of life of the urban population. We can then talk about an economy-oriented interpretation, in which case the goal is to strengthen and support the presence of creative enterprises in the local economy. (Szemző and Tönkő 2015)

. It is important to note that in the field of community culture, the culture- and economy-oriented dimensions are not mutually exclusive, but rather presuppose each other in many cases. Let us take the example of culture-based economic development among the basic services of community culture, which tries to make itself useful in the field of economy with the tools of community culture. Similar to previous theoretical findings, the field interprets individual and community knowledge as a source of creative power, and in this role, organizes and supports programs, activities and services related to the development of culture and the settlement, local business and product development, creative industry, and cultural tourism and supports their implementation (EMMI Decree 20/2018 § 11 (a-c.).

In the following, based on the literature and statistics, we will present the factors and variables that can be used to describe the creative nature of a city, indicatorsm which can characterize the city from the point of view in question. In the following, we organize the indicators into five main groups: we can therefore talk about culture-oriented indicators, public culture-oriented indicators, tourism-oriented variables, but we can also measure the strength of creative economy of the city or the quality of the supporting policy and environment provided by the cities.

Culture-oriented indicators:

- the number of municipal libraries and specialist libraries, the number of their registered readers,

- number of permanent theaters, the number of their performances, the number of their visitors,

- number of cinema halls, number of seats, number of cinema performances, number of cinema visits,

- number of museum institutions, number of their exhibitions, number of museum visitors,

- number of cultural events and number of participants.

In particular, the public culture-oriented indicators:

- number of cultural institutions and community venues,

- number of regular cultural forms, sessions and presentations,

- number of participants in regular cultural forms,

- non-regular forms of education,

- the number of cretive cultural communities, the number of their members,

- number and activities of clubs, circles,

- number of educational events, number of participants,

- trainings,

- national cultural tasks,

- exhibitions, shows, events,

- other services.

Tourism-oriented indicators:

- overall number of nights spent in tourist accommodation,

- number of guest beds in tourist accommodation.

Creative economy-oriented indicators:

- number of registered patents, number of community designs,

- the number of existing and new jobs, and the number of existing and new businesses in the fields of arts, culture, entertainment, media and communication,

- number of graduates from arts and humanities courses, as well as information and communication technology majors,

- number of foreign students at local universities,

- international recognition of universities.

Supporting policy, environmental quality indicators:

- human capital and education, openness,

- tolerance and trust,

- accessibility,

- government and regulations.

New strategic directions, institutional forms and basic services of community culture

Based on the indicators presented above, it can be seen that the culture-oriented and public culture-oriented approaches to the interpretation of the creative city also includes indicators that represent factors found within the framework of community culture.

The number of cultural education institutions and community spaces, the parameters of the professional occupations and participants taking place in them, the cultural events organized in the given settlement, or the number of cultural communities found in the given settlement and their members all determine the quality of a creative cultural settlement. Cultural education and its institutions are thus an integral part of a direction of urban development that creates cities of culture and the arts, as opposed to cities of industry and commerce. Of course, this direction of urban development also requires well-defined organizational, activity, financing and conceptual conditions in the field of community culture. The coherent representations and forms of these needs are the cultural centers and agoras operating mostly in county seats, which meet all the above requirements. These institutions, which are also called flagships in the field of community culture, will be analyzed in more detail.

The significant period of community culture bringing paradigmatic changes after the change of the regime, can be counted from 2012. The National Institute of Culture was at the center of the transformation, the changes and reforms that took place there had a pivotal impact not only on the activities of the Institute, but also on the entire vertical of community culture in Hungary. Without claiming to be exhaustive, let us mention a few elements in these truly paradigmatic changesReconsidering the tasks of community culture in the large system of basic cultural provision The radical renewal of the community culture tasks of the counties, its appearance within the organizational framework, the establishment of its network operation, the transformation of its financing, activity and organizational frameworks of the Institution. Task performance is a project-based transformation that meets the basic expectations of modern public management. Cultural Public Employment Program. The creation of professional trainings, a national training network, the renewal of higher professional training, the launch of the BA course in community coordination in higher education. Launcing national model programs and projects In accordance with the legislative changes, a complete reconsideration of community culture in terms of basic services, institutional types, personnel and infrastructure conditions. The renewal of socialization and volunteering, the initiation and establishment of the collection of Hungarian values in the field. Quality programs of social and economic development in the field. The continuous rise of the cultural norm, the various tender programs, collaborations in the spirit of the common cultural space of the Carpathian Basin.

In the following, we outline the types of community scenes and community cultural institutions and basic services that can be interpreted in the dimension of creative cities, which are the pillars of cultural education activity and the cultural activity of communities.

The basic unit for the provision of community activities is the community scene, which - as a regularly operating institution, facility or complex of premises, or building - enables access to certain basic cultural education services for the population. Its task is to organize community education and provide basic community culture services. In terms of its forms, we are familiar with the community scene that provides a venue for the organization of basic cultural education services, and the integrated community and service space that provides a venue for other activities in addition to the basic services. (Act. 78H § 1-5)

The further organization of basic cultural education services in addition to community arenas is carried out by cultural education institutions.

Based on the legal conditions, the types of public cultural institutions can be the following (Cultutal Act. 77 § 5 para.):

- House of Culture,

- community Center,

- cultural center or agora,

- multifunctional public cultural institution,

- folk high school,

- folk craft creative house,

- children's and youth home,

- Leisure Centre.

The basic community cultural services provided by community cultural institutions are the following (Art. 76 § (3)):

- facilitating the creation of cultural communities, supporting their operation, assisting their development, providing a venue for public cultural activities and cultural communities,

- development of community and social participation,

- providing the conditions for lifelong learning,

- providing the conditions for the transmission of traditional community cultural values,

- providing the conditions for amateur creative and performing arts activities,

- providing the conditions for talent management and development,

- culturally based economic development.

The Agora program

The presentation and analysis of the cultural centers and agoras operating mainly in big cities is of particular importance from the point of investigating community culture and the creative cities. We believe that agoras are focal institutions that can have a pivotal role in the concept and strategic ideas of the creative city. In the following, we will present the development and operational characteristics of this type of public cultural institution.

The source of the name of the program is the city of Athens, where the Agora was a popular place for citizens to spend their time. Public life was also concentrated here, it was the center of orientation and communication. Following the ancient example, in the framework of the Agora and Agora Pólus programs, the largest infrastructural development of culture and community culture was implemented in Hungary in the first step using European Union funds between 2011-2015 (Németh and Szurmainé 2012).

The community culture profession was first able to read about the Agora Program in the Community Culture Strategy for the period 2007-2013 of the Department of Community Culture of the Ministry of Education and Culture (Community Culture Strategy 2007). Among the strategic key areas (pillars) and interventions of Cultural Rural Development and Territorial Development in the Strategy, the Agora Program appeared for the first time, the aim of which is to create multifunctional community centers based on an integrated concept in the case of Hungarian cities with a population of more than 50,000 (Call for Tenders 2008; 2009). In accordance with the above, two large tenders were published in 2008 and 2009.

In 2008, within the framework of the Social Infrastructure Operative Program (TIOP), it was possible to apply for support for the development of innovative cultural infrastructure in Agora Pole and partner pole cities (TIOP-1. 3. 3. 3./08/1). The construction, which is closely related to higher education, was aimed at the development of the infrastructure promoting non-formal and informal learning in the cities of the convergence regions. The overall goal of the construction is to increase the competitiveness of development poles and partner centers with the tools of culture-based urban development. A közvetlen The immediate goal is the foundation of an innovative, complex service-related cultural education institution, founded and maintained by local governments, connected to higher education institutions. It is the so called Agora Pole, which is also suitable for welcoming and providing community services that match the theme of the pole (mechatronics, nanotechnology, life sciences, medicine, etc.) and are adapted to local needs.

The resulting institution will carry out cultural education activities in such a way that it presents the results of regional innovation in an understandable way. In the Agora Pólus institutions, visitors can learn interactively about the fields of science closely linked to the higher education and economy of the city. Thematic dissemination of knowledge can also act as a determining factor when choosing a career. The orientation of students going on to higher educationcan can also be influenced by getting informed about the science and industries that are emphatic, arc an be emphatic in the future based on the strategies in higher education and the labor market offerings of the given development pole In addition, the established institution will help increase interest in the field of technology and natural sciences, contributing to increase the number of graduate students in the given field in the long run.

The Agora Pólus provides an opportunity to make the scientific results and goals of higher education institutions more widely known, and to expand their social and public relations. The Agora Pólus program contributes to the social embedding of the theme of the pole, thereby contributing to the economic innovation development of the country. The winner of the tenders had to create an interactive exhibition space, creative craft rooms, practical showrooms, visualization laboratories, spaces for higher education training and scientific dissemination activities, and institutional infrastructure suitable for hosting conferences. Another mandatory task was the creation of spaces serving community events (e.g., study circles, club sessions, educational presentations, etc.), the creation of a room with at least 15 computer workstations and a broadband Internet connection for the operation of the e-Hungary hotspot, the provision of suitable infrastructure, providing wireless Internet access in public spaces as well as creating a family-friendly environment. When the tender was announced, a budget of HUF 9,108,000,000 was available.

After that, a year later, in May 2009, within the framework of the Social Infrastructure Operative Program of the New Hungary Development Plan, the call for tenders was published, in which it was possible to apply for the development of the infrastructure of AGORA - multifunctional community centers and regional community culture advisory service (TIOP-1. 2. 1 /08/1).

The overall goal of the construction is to mitigate the differences in cultural and infrastructural development between individual regions and areas through culturally based urban development. The creation of a system of public cultural institutions that creates an opportunity to provide better quality cultural services, by linking community culture and public culture systems, improving the conditions of lifelong learning and creating and developing its infrastructure. In this case, the achievement of the above goals will be ensured by the creation of the Agora institution.

According to the ideas, the Agora is a multi-functional community center, cultural education institution, which, in a specifically designed built environment, is suitable for the integration of community-cultural, educational-adult training and experience functions, offering rich cultural services along with these functions for the socio-cultural development of the the local society or the city. Its operation directly and indirectly affects the community culture of the population living in the wider geographical area, providing high-quality programs, service and methodological assistance to the cultural education institutions of the surrounding settlements and sub-regions.

Three main goals for the establishment of the Agoras were stated in the document. On the one hand, the creation of a multifunctional community center by rationalizing the cultural education institutions operating in the city. Secondly, the installation of community, adult education and experience functions in one complex, providing access to the widest possible spectrum of services in one place. Thirdly, the establishment of a regional community culture advisory service function, thereby providing the basic cultural and cultural education services of the surrounding micro-regions at a higher levelThe target group of the development realized within the framework of the project is the population using complex cultural services, and in terms the professional services, the network of cultural education institutions within the scope and their users. (Németh and Szurmainé 2012.)

Within the framework of the New Hungary Development Plan and the New Széchenyi Plan, in about five years - between 2011 and 2015 - as a result of investments and developments, agora and agora pole-type investments were made in 13 settlements.

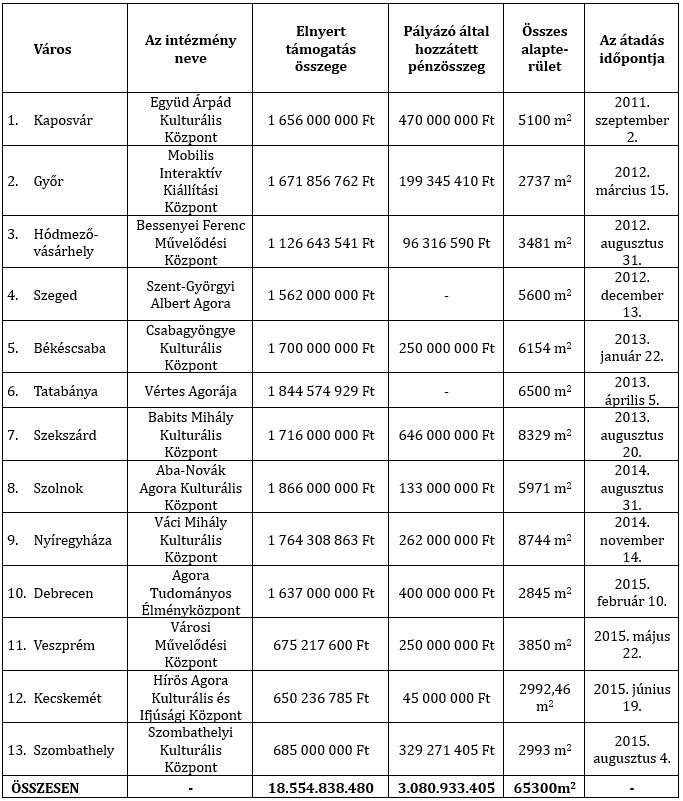

Table 1. Agoras in Hungary

(Source: based on Németh 2015)

According to the table, Agora was established in 7 settlements (Békéscsaba, Hódmezővásárhely, Kaposvár, Nyíregyháza, Szekszárd, Szolnok, Tatabánya), and Agora Pólus was established in 6 settlements (Debrecen, Győr, Kecskemét, Szeged, Szombathely, Veszprém). The cultural historical and community cultural professional importance of the developments is shown by the fact that the investments cost more than HUF 20 billion. The floor area of the cultural centers totaled 65,000 m2.

Based on all of this, it can be stated that even from the action draft of a creative city concept, we could have read the goals or functions that the Agora program represents and acomplishes, that is, we can discover common points between the strategic aspirations of the concept supported by the European Union and envisioned by several cities and smaller settlements and the work carried out by community culture and all its institutions, with special emphasis on the Agora program. These common points can lead to collaborations and the triggering of synergy effects if we highlight them and take steps to them.

Conclusion

The creative city is home to culture and communities. The cultural life taking place in the creative city generates new ideas in an inspiring way, giving new impetus to the work of creative enterprises, creative individuals and communities. At the same time, the culture-oriented approach to the interpretation of the creative city also includes indicators that are closely related to community culture and the conditions provided by its institutions, mainly in big cities. In other words, the concept and implementation of the creative city is, and can be, well served by the field of community culture with its activities, organization and infrastructure. Community culture and its institutions can thus be an integral part of a direction of urban development that creates in cities of culture and the arts, as opposed to cities of industry and commerce. In the creative city as a strategic development direction, exactly these basic cultural elements appear as prominent factors. A strategic direction is given, which enjoys the support of the European Union, and it is a popular and desired vision of the settlements. A vision that places more emphasis on human capital, communities and culture than that of the cities of industry and commerceWe believe that in the process of the evolution of this city, community culture has a first-class role, as it has the network of institutions and expertise that is the basic scene and support for cultural activities and the creation and maintenance of urban communities. Thus we have common connection points that provide an opportunity for cooperation. One, perhaps the most important, of these is the common goal of creating modern, creative cities. In order to achieve the common goal, it is worth continuing to cooperate or start thinking together with the decision-makers of the cities. This will certainly lead to further results for both creative cities and community culture.

References:

- Allen, K. – Hollingworth, S. (2013): ’Sticky Subjects’ or ’Cosmopolitan Creatives’? Social Class, Place and Urban Young People’s Aspirations for Work in the Knowledge Economy. Urban Studies, 50. évf. 3. szám, 499-517. p.

- Andersson, A. (2011): Creative people need creative cities. In: Andersson D. E. - Andersson A. E. - Mellander C. (eds): Handbook of Creative Cities, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. 14–55. p.

- Bianchini, F. (1993): Remaking European cities: the role of cultural politics. In: Bianchini, F. – Parkinson, M. (eds.): Cultural Policy and Urban Regeneration: The West European Experience. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1–20. p.

- Byrne, Tara (2012): The creative city and cultural policy. Opportunity or challenge? In Cultural Policy, Criticism and Management Research 6, pp. 52–78. p.

- Enyedi Gy. (2005): A városok kulturális gazdasága. In: Enyedi Gy. - Keresztély K. (szerk.): A magyar városok kulturális gazdasága. MTA Társadalomkutató Központ, Budapest. 13-27. p.

- Flew, T. (2012): The creative industries: Culture and policy. London: Sage Publications.

- Florida, R. (2002): The Rise of the Creative Class. Basic Books, New York.

- Florida, R. (2005): Cities and the Creative Class. New York and London: Routledge.

- Galloway, S. - Dunlop, S. (2007): A Critique of Definitions of the Cultural and Creative Industries in Public Policy. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 13 évf. 1. szám, 17–31. p.

- Karvounis, A. (2010): Urban creativity: the creative city paradigm. AthensID, 8. évf., 53–81. p.

- Kooijman, D. - Romein, A. (2007): The limited potential of the creative city concept: policy practices in four Dutch cities Presented at the ‘Regions in focus’ conference, Lisbon. 1-47. p.

- Landry, C. (2000): The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators. Comedia/Earthscan, London.

- Közművelődési Stratégia (2007-2013). Oktatási és Kulturális Minisztérium Közművelődési Főosztály.

- http://epa.oszk.hu/01300/01306/00092/pdf/EPA01306_Szin_2007_12_04_szeptember_002-026.pdf. Letöltés: 2021. 06. 09. 11.56.

- Németh J. I. – Szurmainé S. M. (szerk.): A magyar közművelődésről. 2012. Arcus.hu Kft., Vác.

- Német János István (2015): Közösségépítő Agorák Magyarországon. Terek – Emberek – Közösségek. Budapest, Nemzeti Művelődési Intézet.

- Pályázati Felhívás 2008. (TIOP-1. 3. 3./08/1.) Agóra PóLUS – Pólus- illetve társpólus városok innovatív kulturális infrastruktúra fejlesztéseinek támogatása. https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/doc/1084. 2017. 05. 02. 11.11.

- Pályázati Felhívás 2009. (TIOP-1.2.1.A1-15/1.) Agora – Multifunkcionális közösségi központok és területi közművelődé-si tanácsadó szolgálat infrastrukturális feltételeinek kialakítása - Kísérleti, településcsoportos Agora fejlesztés Pályázati Felhívás. https://www.palyazat.gov.hu/node/56771 2017. 05. 19. 11.43.

- Pratt, A. C. (2011): The cultural contradictions of the creative city. City, Culture and Society, 2. évf. 3. szám, 123-130. p., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2011.08.002

- Scott, A. J. (2014): Beyond the Creative City: Cognitive-Cultural Capitalism and the New Urbanism. Regional Studies, 48. évf. 4. szám, 565-578, DOI: 10.1080/00343404.2014.891010.

- Szemző H. - Tönkő A. (2015): Kreatív városok – jó gyakorlatok. Városkutatás Kft., Budapest.

- The Cultural and Creative Cities Monitor Edition, 2017.

- Tokatli, N. (2011): Creative Individuals, Creative Places: Marc Jacobs, New York and Paris. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35. évf., 1256-1271. p. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01012.x.

- Ulldemolins J. R. (2014): Culture and authenticity in urban regeneration processes: Place branding in central Barcelona. Urban Studies, 51. évf. 14. szám, 3026–3045. p.

- Pályázati felhívás a Társadalmi Infrastruktúra Operatív Program keretében – AGÓRA.

- Szirmai Viktória (2007): A magyar nagyváros térségek társadalmi jellegzetességei. Magyar Tudomány, 6. szám, 740-748. p.

Acts:

- 1997. évi CXL. törvény a muzeális intézményekről, a nyilvános könyvtári ellátásról és a közművelődésről. (Kultv. • CXL of 1997. Act on museum institutions, public library services and community culture. (Cult.

- 20/2018. (VII. 9.) EMMI rendelet a közművelődési alapszolgáltatások, valamint a közművelődési intézmények és a közösségi színterek követelményeiről. • 20/2018. (VII. 9.) EMMI Decree on the requirements of basic public cultural services, as well as community cultural institutions and community arenas.