Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer: Our intellectual cultural heritage through the work of a blue-dyer family from Győr (Part I)

Cikk letöltése: pdf2021-04-01

„Where there is no traditional form, neither religion nor art can develop.”

Béla Hamvas: Five geniuses

Abstract: In my study I am introducing a blue-dying workshop of Győr, where they are making the textiles with original tools and technology until the present day. At the same time, I am pointig out the family history of the blue-dying family Éhling, which spans 5 generations. In addition, with the help of the interviews I have made with Ildikó Tóth, who has gained the title ’Master of Folk Art’ recently, and her family, I am presenting their excellent work done in the survival of our cultural heritage, education and community development. In 2018, proposed by five countries including Hungary, blue-dying was recognised as a traditional craft, and it appeared on the list of intellectual cultural heritage of UNESCO, in the elaboration of which Ildikó Tóth and her family also participated. In my study I am touching upon this as well, and I am also publishing the true stories about blue-dying masters, the trade and the family.

Introduction

As a teacher and ethnographer, I have always been interested in folk crafts and handicraft techniques. At my first workplace, at the Children's House of Győr, I often organized playhouses and folk craft demonstrations as a folk dance teacher, where I got to know famous folk artists and various handicraft techniques. At our university, I still teach folk crafts in theory and practice. I am pleased to say that our trainee teachers and special education teacher trainees enjoy felting, sewing, beading, or "daub" eggs for Easter. I have always been interested in blue dyeing, and we often visit the Blue Dyer Workshop of Győr with our students, where they can learn about this beautiful craft and even try out the technique. My choice of topic was inspired by this, as well as the fact that the "Tradition of blue dyeing" is recognized both at the county and international level. Ildikó Tóth and her family helped me prepare my publication, they shared their family stories with me, showed me their memory documents and presented their craftsmanship and the contemporary ways of its transmission.

Blue dying as a value

My interviewee, Ildikó Tóth, defined the present day blue dyeing technique as follows: "Blue dyeing is a special textile dyeing process: It spread to a greater extent in the 18th century. It has two main work phases: applying a covering material (so-called "pap" in Hungarian) to the surface of the textile with the help of pressure molds (crutches). Coloring in indigo bate in a dyeing pool sunk into the ground or in a tub in indatré bate.”[1]

In 2003, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) adopted the Convention on the Preservation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Its objective is to preserve the intellectual cultural heritage, to respect the intellectual heritage of the concerned communities, to raise awareness of the importance of heritage at the local, national and international level (Csonka-Takács 2013).

To our delight, based on the recommendation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Committee of the Hungarian National Committee of UNESCO, the tradition of blue dyeing in Hungary - thus the activities of the blue dyers of Győr - was included in the National Register of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2015.

Picture 1: Document confirming this

(Photo: Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer, Győr, 2020)

And in 2018, at the proposal of five countries, including Hungary, the above mentioned traditional craft was recognized and added to the List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of UNESCO. It was also a beautiful example of the cooperation of different nations, because Austria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Germany and Slovakia submitted their nomination together. I would like to note that this is the second time that Hungary participated in a joint submission, because falconry as a living human heritage had been submitted together with 18 countries. The ceremonial announcement and handing over of the document certifying that the "Tradition of Blue dyeing" was added to the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity took place on February 12, 2019, in the Blue Dyer's Museum of the Count Esterházy Károly Museum in Pápa. At the ceremony, the UNESCO document certifying the admission was handed over to the blue-painting workshops of Hungary by Dr. Eszter Csonka-Takács, the director of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Board. Besides, the Blue Dyeing Museum of Pápa and Dr. Ottó Domonkos, an ethnographer and an excellent expert of the subject were also rewarded.

Picture 2: Document authenticated by the General Director of UNESCO on the wall of the family shop

(Photo: Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer, Győr, 2020)

Picture 3: Receiving the UNESCO certificate in the Blue Dyeing Museum of Pápa.

Next to the blue dyers, Dr. Ottó Domonkos can be seen on the right side of the picture and the fifth from the right is Ildikó Tóth.

(Photo: Farkas-Balázs Mohi, Pápa, 12/02/2019)

There are currently six blue dyeing workshops operating in Hungary: the workshop in Bácsalmás, Győr, Nagynyárád, Szombathely, Tiszakécske and Tolna. I personally met two of these workshops and their masters. In 2019, I managed to visit the Kossuth Prize-winning blue dyer Miklós Kovács' workshop in Tiszakécske[2]. The other master, Ildikó Tóth also participated in the development of the "Tradition of Blue dyeing" component. I have known her for a long time and I can consider her a friend. During my research on the ballad Mári Dely she even turned out to be a relative of mine.[3] In our county, and even in the region, she and her family are now the only ones dealing with blue dyeing.

The blue dyers of Győr

As Ottó Domonkos, an excellent researcher on the topic, wrote: "The history of European textile printing – including blue dyeing – has a library of literature..." (Domonkos 1981: 7). My choice of topic was also justified by the fact that, with one exception, no details were published about the dying family from Győr. In 1998, Ferenc Bakó published an interview with the master Péter Éhling, who was the founder of the workshop in Győr. (Bakó 1998: 161-171).

"We have information about the first authentic practice of textile printing from 1695." (Domonkos 1981: 13). In the recorded minutes of the council of Győr, the names of two linen printers are listed: "György Balogh" and "Mihály Fábián." Therefore we already have data on the settling down of linen printers responding to the needs of Győr from this time.

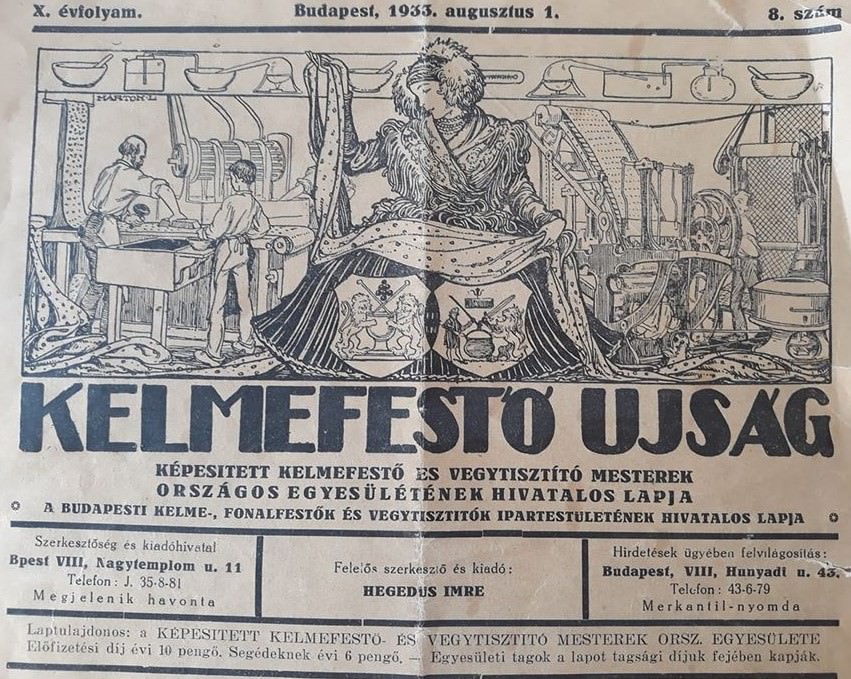

The first written Hungarian mention of the term "blue dyer" dates back to 1770" (Domonkos 1981: 27), namely in a letter of a complaint in Pápa. By the middle of 18th century, there was a dyer master in every city, including Győr, and a new process of textile dyeing, reserve pressure blue dyeing, could be launched.[4] For this, it was necessary to switch from the use of traditional woad to the use of more color-fast, more effective indigo and to the cold indigo bate process. The journeys of the master students also helped spread new procedures. "In the old days, when they did not dye with indigo, but with woad, they used human urine. Urine was collected in stone containers. But only urine before reproductive age was good. This is how the color was developed.” - says Ildikó. Since indigo was less known in the beginning, it was called as a "devil's dye", "Teufelsaugé". As Ottó Domokos writes in his book, in our county, there is information about the new procedure from the family chronicle of the dyer master, Jakab Kistler from Sopron from the 70s of the 18th century. [5] The presence of dyers in Győr is revealed by the fact that "in 1831, the city council named a street after the painters. The famous baize and fabric painters worked here." Ottó Domonkos also mentions that: "There is also Festő street (Dyer's street) in Győr, Veszprém, Szeged, and Kecskemét, as painters have always worked in these places." (Domonkos 1981: 40). This was also confirmed by Ildikó: "My great-grandfather lived at 12 Festő street and worked with a partner dyer named Mészáros. It used to be a beautiful arcaded house. At the bottom of one of the dyeing baths, the date of 1854 can be read, so dyeing was present then." The fact that they even had a magazine (Hungarian Fabric Dyer Newspaper 1909-1913, Fabric Dyer Newspaper (1934-1944)) which also belonged to the Éhling family can also prove the presence of dyers in large numbers. The family owns another copy published in 1933. I note that on the publications of the expert magazine published from 1934, the word blue dyer no longer appears in the title.

Picture 4: Hungarian Fabric Dyer Newspaper (1909-1913)

Picture 5: Fabric Dyer Newspaper (1934-1944)

Picture 6: The newspaper of 1933, in the property of the family. The coats of arms and the process of blue dyeing are clearly visible

Picture 6: The newspaper of 1933, in the property of the family. The coats of arms and the process of blue dyeing are clearly visible Thus, the street in Újváros[6] was named Festő street after the master dyers who lived and worked here. "Earlier, the noisy, smelly crafts were put out in the suburbs. Like cloth dyers, tanners, and nail smiths." Ildikó even showed me the lion stone that can still be seen at the beginning of the street. "If we turn into Festő street, one of the stone lions can still be seen in front of the Puntigám house.[7] It is a boundary stone, a wheel-throwing marble stone. There is a saying here: from here to Puntigám or over. Craftsmen and musician gypsies lived on the other side of Festő street." What is more, I was enriched with a story of belief during the interview: "The coat of arms of the dyers is the lion. In the coat of arms of the blue dyers, there is a large blue dyeing cauldron, the dyer's stick, the indigo breaker in the middle and two lions standing on the sides. The masters believed that since it was their emblem, the lion would protect them from all the misfortune. In Győr, the entrance to Festő street is still guarded by a stone lion on one side in front of the Puntigám house. The old masters say that there will be dyers, this craft will not die out as long as a lion guards Festő street." Picture 7, 8: A stone lion at the entrance of Festő street in Győr

Thus, the street in Újváros[6] was named Festő street after the master dyers who lived and worked here. "Earlier, the noisy, smelly crafts were put out in the suburbs. Like cloth dyers, tanners, and nail smiths." Ildikó even showed me the lion stone that can still be seen at the beginning of the street. "If we turn into Festő street, one of the stone lions can still be seen in front of the Puntigám house.[7] It is a boundary stone, a wheel-throwing marble stone. There is a saying here: from here to Puntigám or over. Craftsmen and musician gypsies lived on the other side of Festő street." What is more, I was enriched with a story of belief during the interview: "The coat of arms of the dyers is the lion. In the coat of arms of the blue dyers, there is a large blue dyeing cauldron, the dyer's stick, the indigo breaker in the middle and two lions standing on the sides. The masters believed that since it was their emblem, the lion would protect them from all the misfortune. In Győr, the entrance to Festő street is still guarded by a stone lion on one side in front of the Puntigám house. The old masters say that there will be dyers, this craft will not die out as long as a lion guards Festő street." Picture 7, 8: A stone lion at the entrance of Festő street in Győr

Photo: Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer, Győr, 2020

Several families of dyers worked in this street. In 1950, Péter Éhling mentions the names of Aschendorfer, Sáfrány and Potfai as masters to Ferenc Bakó. "The Potfai family had six houses in the street." Ildikó's great-grandfather often said: "A dyer can never be a poor man, but he works a lot for it."[8] I must add that it is regardless of the fact that the German equivalent of the blue dyer (Blaumachen) also means a do-nothing - I learned this from Ildikó's husband Zsolt Gerencsér: “The German term is Blaumachen (do-nothing). This comes from the fact that when the textile is lowered into the dyeing bath or well, during blue dyeing, it must be there for 15 minutes, and then it must be pulled up and we should wait at least 15 minutes for it to oxidize in the air. During this time, practically nothing can be done. When the master stood at the door and was asked what he was doing, he said: »Ich mache blau«, which means I'm making blue, and that meant, nothing now, I have time. This term is still in use today and it comes from blue dyeing.”In the collection of Ferenc Bakó - when talking about the picture depicting the process of blue dyeing - the name of another master from Győr is mentioned. "The pictures that hung on the wall of Schiffer's former blue dyeing workshop in Győr and that were painted on tin plates, present the blue dyeing work as they were once done in Schiffer's workshop by the master and his 28 assistants." (Bakó 1998: 168). From him, the above mentioned master, "Aschendorf took over the workshop at 1 Festő street, whose grandson was the famous writer and aesthete Béla Hamvas".[9]

Several families of dyers worked in this street. In 1950, Péter Éhling mentions the names of Aschendorfer, Sáfrány and Potfai as masters to Ferenc Bakó. "The Potfai family had six houses in the street." Ildikó's great-grandfather often said: "A dyer can never be a poor man, but he works a lot for it."[8] I must add that it is regardless of the fact that the German equivalent of the blue dyer (Blaumachen) also means a do-nothing - I learned this from Ildikó's husband Zsolt Gerencsér: “The German term is Blaumachen (do-nothing). This comes from the fact that when the textile is lowered into the dyeing bath or well, during blue dyeing, it must be there for 15 minutes, and then it must be pulled up and we should wait at least 15 minutes for it to oxidize in the air. During this time, practically nothing can be done. When the master stood at the door and was asked what he was doing, he said: »Ich mache blau«, which means I'm making blue, and that meant, nothing now, I have time. This term is still in use today and it comes from blue dyeing.”In the collection of Ferenc Bakó - when talking about the picture depicting the process of blue dyeing - the name of another master from Győr is mentioned. "The pictures that hung on the wall of Schiffer's former blue dyeing workshop in Győr and that were painted on tin plates, present the blue dyeing work as they were once done in Schiffer's workshop by the master and his 28 assistants." (Bakó 1998: 168). From him, the above mentioned master, "Aschendorf took over the workshop at 1 Festő street, whose grandson was the famous writer and aesthete Béla Hamvas".[9]

Over time, the number of blue dyers decreased: "While there were 414 of them in 1890, around 1940 there were only 70 independent workshops in the country." (Domonkos 1991: 388). The Trianon peace decree did not do good to this craft either. Several workshops lost their markets and their access to fairs. This is also true for the masters of Győr. As Ildikó describes: "In the heyday of the craft, until World War II, dyers held their annual gatherings in Budapest every year. Our family keeps a photo of this from 1945."

Picture 9: Blue dyeing meeting. Budapest, 1945. All the three blue-painting families of Győr can be seen here. On the left Péter Éhling with his three daughters

(the mother of the 7-year-old Ildikó Tóth, Mrs. Józsefné Tóth). Opposite them the widow, Mrs. Romanek and her son József Róka, and Péter Berecz, blue dyer.

(Source: the website of the Blue dyer Workshop)

Ferenc Bakó writes about the blue dyers of Győr that they were left out of the register of 1946, and he believes that the reason for this can be that they were presumably classified as fabric dyers and dry cleaners, probably because the profession was declining. "In 1954, my great-grandfather donated most of his printing boards to the Xantus Museum of Győr, only a few were kept and the family mainly switched to textile dying. This was due to the fact that factory production started, women stopped wearing national costumes and the Swabians who were wearing the blue-dyed clothes were deported." [10] In 1963, Frigyes Grábits, tailor, listed three blue dyers in Győr for Ferenc Bakó: "Péter Ehling and Péter Berec who were over 80, and a younger "fabric dyer" named Róka. (Bakó 1998: 162). "The Róka family came to Győr after Trianon, their original name was Romanek." – Zsolt revealed it to me.

Pictures 10 and 11: The dyeing workshop of the Róka (Romanek) family in Festő street, GyőrThe initials "VR"= Vitéz Róka (Vailan Fox) is still visible on the door

(Photo: Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer, Győr, 2020

Due to the proliferation of textile factories from the second half of the 20th century, few workshops were able to survive. In the 1970s, their number did not even reach thirty, and in the 1990s only fifteen masters worked in this profession. (Domonkos 1991: 391). Disrobing and abandoning the national costume did not do good to this craft either. The workshops closed down, however, blue dyeing still continued for centuries. The introduction of indantrene and its good properties helped the demand for linen materials. As a positive example we can mentioned that in 1962 The Blue Dyer's Museum was established in Pápa, on the site of the workshop of the Kluge company, which played a major role in preserving and popularizing blue dyeing as a craft.

Pictures 12 and 13: With trainee teachers in the Blue Dyer's Museum of Pápa

(Photo: Zsuzsanna Lanczendorfer, Pápa, 1996.)

Summary

As it became clear from the literature and the interviews, this old beautiful craft has been present in Győr since the 17th century, according to the first data. Several families (e.g.: Aschendorfer, Balogh, Berecz, Éhling, Fabian, Potfai, Róka, Sáfrány, Schiffer) practiced this profession, which provided a living for many masters. Sometimes ingenuity helped to survive: "A lot of water was needed for fabric dyeing. This was a there in Győr. However, around 1908 the Rábca was diverted, so several masters stopped this craft. My great-grandfather did not despair, he had the water laid into the street, so he could continue his craft."[11]

Negative historical processes (wars, deportation), the industrial development, and changes in the tastes of the people have also significantly reduced the number of people practicing this craft. In our county, and even in our region, only Ildikó Tóth and his family deal with blue dyeing. You can read about their value-preserving activity, about the transmission of the family craft, their role in education and cultural education in the next part.

Interviewes:

- Zsolt Gerencsér: born in Győr, 1969. (Young Master of Folk Art)

- Tóth Ildikó: born in Győr, 1962. (Master of Folk Art)

References:

- Bakó Ferenc (1998): Adatok a győri múzeum kékfestő gyűjteményéhez. In: Szende Katalin – Kücsán József (szerk.): „Isten áldja a tisztes ipart.” Tanulmányok Domonkos Ottó tiszteletére. Sopron, A Soproni Múzeum kiadványai 3. 161- 171. p.

- Domonkos Ottó (1981): A magyarországi kékfestés. Corvina Kiadó. Budapest.

- Domonkos Ottó (1987): Kékfestő, föstő. In: Ortutay Gyula (főszerk.): Magyar Néprajzi Lexikon. 3. Budapest, 118-120. p.

- Domonkos Ottó (1991): Kékfestés. In: Domonkos Ottó (főszerk.): Kézművesség. Magyar Néprajz III. Budapest, 386-391. p.

- Csonka-Takács Eszter (szerk.): A Szellemi kulturális örökség nemzeti jegyzéke és a jó megőrzési gyakorlatok. Szabadtéri Néprajzi Múzeum, 2013.

- O. Nagy Gábor (1982): Magyar szólások és közmondások. Gondolat Kiadó. Budapest

- Tajti Erzsébet (2009): A kécskei kékfestő család. Tiszakécskei Honismereti Kör, Tiszakécske

- www.gyorikekfesto.hu › 08_open letöltés: 2020. 08. 10.

- http://www.gymsmo.hu/cikk/megyei-ertektar-megyerikumok.html letöltés: 2020. 08. 100.

- Magyar Kelmefestő Ujság 1909-1913. Kelme,- kék,- fonálfestők, vegyi tisztítók és fehérítők lapja. A Magyarországi Kelmefestő és Vegytisztító Munkások és Munkásnők Egyesületének vasárnaponként megjelenő hivatalos közlönye.

- Forrás: https://adtplus.arcanum.hu/hu/collection/BME_MagyarKelmefestoUjsag/letöltés: 2020. 08. 13.

- Képesített Kelmefestő és Vegytisztító Mesterek Országos Egyesületének és a Budapesti Kelme-, Fonalfestők és Vegytisztítók Ipartestületének hivatalos lapja. (1934-1944) Forrás: https://adtplus.arcanum.hu/hu/collection/BME_KelmefestoUjsag/letöltés: 2020. 08. 13.

[1] The texts of the interviews are marked in italics.

[2] The workshop of master Miklós Kovács is a few kilometers from the Lakitelek Folk High School. Many thanks to Erzsébet Tajti, a teacher and local history researcher, and Péter Szűcs, the head of the Győr-Moson-Sopron County Directorate of the Hungarian National Institute of Culture for helping me to get to know the master!

[3] Mári Dely's ballad was added to the Győr-Moson-Sopron County Value Repository in 2015. I note that the heroine of the ballad was my relative.

[4] In the 18th century, the so-called Porcellan Druck, a technical term denoting a reserve print imitating the color effect of oriental blue-and-white patterned porcelains, referred to blue dyeing."Domonkos 1991: 387.

[5] I must note that if they were not sufficiently diluted, the sulfuric acid could tear the canvas apart. Domonkos 1981: 24.

[6] A district of Győr.

[7] name of a merchant family.

[8] Ottó Domonkos mentions only one reported blue-dyer from Győr, László Róka. Domonkos 1981: 97.

"The dyer earns white money with his black hands = fabric dying is a profitable occupation." See: O. Nagy 1982: 212.

[9] Ildiko Tóth.

[10] Ildiko Tóth. I write the name Éhling according to the records. e.g.: Ferenc Bakó wrote Ehling in his study.

[11] Tóth Ildikó.