Balázs Benkei-Kovács – Julianna Farkas – Barbara Keszei – Csaba Hédi – Andrea Hübner – Anna Popcsa – Orsolya Thuma: Inhabitants’ reaction and attachment to local values. A case study of three hungarian towns

Cikk letöltése: pdf2021-11-21

Absztrakt: Kutatásunkban három település, Fót, Göd és Vác lakosai körében vizsgáltuk a helyi értékek ismeretét, az azokhoz való érzelmi hozzáállást, illetve, hogy ezek összefüggései hogyan befolyásolják a kulturális és természeti örökségek értékelését. Kvalitatív (kérdőíves) és kvantitatív(interjú) módszerrel dolgoztunk: a kérdőíves eredményeket SPSS statisztikai elemzéssel, az interjúkat narratíva elemzéssel értékeltük. Tanulmányunkban a magyar és nemzetközi szakirodalom új és legújabb szociológiai, pszichológiai, antropológiai és szociálpszichológiai megközelítéseinek keretében vizsgáltuk a kérdéses jelenségeket. Az adott társadalmak érték felfogását, az érzelmek szerepét örökségi értékek megítélésében és az önazonosság tekintetében, a kulturális emlékezet gondolatát, valamint az örökséginterpretáció elméletét és gyakorlati kérdéseit értelmeztük egymással is összefüggésben.

Abstract: In our research we investigated how inhabitants of three Hungarian towns, Fót, Göd and Vác respectively relate to their hometowns in terms of emotions and knowledge and how these factors affect each other in turn in their appreciation of local values of heritage. The methods applied were both quantitative (questionnaire) analysed with SPSS program and qualitative (interviews)examined with narrative analysis.

Sociological, psychological, anthropological, and social psychological theories served as guiding frameworks examined in mutual relation to one another. Our interpretation has learnt a lot from the academic review on the meaning of value and society, the role of emotions in people’s reaction to and perception of heritage in self-identification as well as the study of cultural memory and the contemporary idea and practice of heritage interpretation, all made possible utilizing the wide array of these sources serving as theoretical background of the research project.

A kutatási folyamatot és a tanulmány elkészítését a Nemzeti Művelődési Intézet Közművelődési Tudományos Kutatási Program kutatócsoportok számára alprogramja támogatta.

The research process and the preparation of the study were supported by the sub-program of the Cultural Research Program for Research Groups of the National Institute of Culture.

1. The meanings of value

1.1. Value and society

Value comes from the relationship of humans to their inner and outer worlds. It means the perception of something as essential and important or of some kind of priority, desire or achievement (H.Farkas 2006) Things we lack automatically become more important stimulating and motivating us to fill in the gap and cease the need. (Loránd 2002)

Since values create a hierarchy the Maslow hierarchy of needs is worth being revisited in close connection to this. Hankiss claims there are two types of values: objective values are the ones that a given system needs to operate itself whereas subjective values are the ones perceived and set by the system itself as essential. (Hankiss 1977)

According to Rudolf Andorka values are to be considered in terms of a given social context since what we consider good or bad, useful, or wishful highly depend on the society’s specific socialization patterns. (Andorka 2006)

On the basis of World Value Survey 5 TÁRKI Social Research Institute underlines that Hungary like all the other countries is determined by its history and cultural heritage that are fundamentally those of Western Christianity which means that the national community belongs to the Western Christian world although - as Tóth claims- in an „insular society” (to be characterized by occlusion, rationality and secularity) on the edge of this cultural group. (Tóth 2009).

After the change of the regime in1989 and the EU accession in a society getting and called „plural” by Bábosik (2001) a person can belong to various groups among them ones that help individual fulfilment and others that serve community benefits.

1.2. Culture, cultural value, cultural heritage

Edward Burnett Tylor the founder of the study of cultural anthropology defined culture or civilization in 1871 as a complexity including a lot of fields like knowledge, belief, arts, morals, law, capacities and skills acquired by a person in the process of socialization (Grad-Gyenge–Kiss et al. 2018). Malinowski claimed culture to be a set of tools provided for individuals that help them overcome concrete problems permanently arising while Kroeber and Kluckhohn had a view in the 1940s that culture is made up of behaviour patterns people can get access to through symbols (Grad-Gyenge–Kiss et al. 2018) Social psychologist Geert Hofstede defined culture by synthetizing the Kroeber–Kluckhon theory saying culture is rather a collective cognitive program differentiating human communities from each other (Grad-Gyenge–Kiss et al. 2018)

Norbert Elias in his book The Civilizing Process underlines that although the terms culture and civilization are often used as synonyms some differentiations are possible to be made. While culture is a term specifically relating to the concept of the nation with mental, artistic and religious products and their quality, civilization is a global term primarily regarding technical development and its level (Elias 2004).

Iván Vitányi was one of the first to call attention to the phenomenon that mass communication has become a third sociocultural sphere in addition to high culture and popular culture. This resulted in the disintegration of tradition causing value system, ideals, morals, and national self-image to become uncertain (Vitányi 2006).

2. Emotions and heritage interpretation

2.1. The role of emotions

The role of emotions had been increasingly considered in the study of cultural values and the narratives related to them (Smith – Campbell 2015) It is evident now that to understand cultural traditions it is important to see how emotions operate. One of the goals of cultural heritage sites is to make and let people experience certain emotions in connection to the places of significance where they can reflect upon present and past. Several emotions may arise in the visitor from anger to happiness and joy, from fear to strengthened self-esteem, from nationalism to truly experienced patriotism and from sadness to compassion. Without deeper elaboration the visit might simply remain on the level of a nice outing.

Emotional experience is a composite phenomenon resulting from the specialities of the place, the personality of the visitor and the social context respectively whereas it also depends on how much the person can recognize his/her own emotional reactions and how s/he can handle them (Mayer et al. 2008)

Nyaupane and Thimothy (2009) claimed that the knowledge of cultural heritage, the appreciation of its significance and the visit to the place all have an impact on attitudes in connection to its preservation. Visiting the places increase consciousness towards the site and a wish to preserve it.

2.2. Values, behaviour and heritage interpretation

Values we consider important determine our goals and define our behaviour. Bardi and Schwartz (2003) examined how 10 general human values correlate with behaviour. Schwartz and Sagiv (1995) listed these 10 values under 4 higher categories along a wheel showing similar features closer to each other while some values are performed as irreconcilable with certain characteristics.

Heritage interpretation is about the performance and interpretation of cultural and natural heritage as well as about the handling of reactions, resolution of controversies and exploration of possible narratives. Since heritage is often controversial depending on who explores the meaning, interpretation considers the role and forms of expressions of emotions with great attention. The interpretative activity often works with the tools of gamification, edutainment, and experience pedagogy.

Interpretation contains two layers in mutual connection to each other: there is a universal value system the given heritage carries and a conglomeration of subjective meanings the visitor can identify with making heritage relevant for himself/herself. Earlier interpretations Smith (2006) calls authorized heritage discourse sentimentally handle heritage as old, nice and mainly of material culture mostly of Western tradition. The new wave of interpretative approach claims explorative approach helps visitors achieve experience that makes them sensitive towards the values of the site making them appreciate what they see.

The visitor and the interpreter are not the sole players in an ideal case. Bangall calls emotional authenticity the past and present of the members of the local community embodied and encapsulated in an object, in a site or in a tradition getting shape through individual story telling (Bangall 2003).

Not only the local communities but also the visitors can react with even extreme emotions to heritage sites (Wells – Butler – Koke 2013). Facing the past can cause present recognitions concluding into the need of emotional elaboration. Emotions are born in an interaction with the place always in social and cultural context and get elaborated by the capacity of the visitors to control and handle their emotions in relation to the site. Professionals can have an important role in handling and channelling the emotions. (Smith 2015).

2.3. Memory versus cultural memory

In our research memories -either of someone’s own or those of ancestors- proved to be important factors in their perceptions of values and in how they emotionally related to them.

Like emotion memory is also something that does not just exist as such but is highly mediated and reconstructive (Wertsh 2002). Emotions do not only play a great role in the interpretation of memory but themselves are representational qualities as Sue Campbell puts it (2006:373). Alan Morton (2013) speaks about emotional truth meaning a knowledge that is not made up of clear data but can have several outcomes depending on individual understandings. Smith claims heritage sites are not to be considered in their own reality, but their main function is to bring memory alive. Since cultural heritage is a „unique and irreplaceable property” of a community the study of collective memory is of utmost importance. The inclusion of communities is unavoidable especially in cases of „sites of conscience” (Sevcenko 2002).

Although discourses of cultural memory studies in history, literature, art history and cultural anthropology, etc. seem to be navigated in different channels than heritage interpretation the theoretical origin of both have the same root. Although the topic of cultural memory is widely linked to Jan Assmann due to his book Das Kulturelle Gedächtnis. Schrift, Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen (1992)(Cultural Memory and Early Civilization) in fact he continued to reveal the theory started by Maurice Halbwachs in his book La Topographie Legendaire des Evangiles en Terre Sainte (The Legendary Topography of the Holy Land).The central idea of the theory is, that memory is a socially defined historical construction sustained by certain social groups or people in power. Certain events and holidays are privileged whereas others are let to be forgotten. One of the main questions of the study of cultural memory is what things must not be forgotten (Assmann1991:30) You will remember things that can adequately be inserted into the collective memory hence seems to be understandable. Things with no frames of reference in the present will be forgotten. Group memories can build together into personal memories. Cognition can be individual, but memory is always related to groups. After Halbwachs, Assmann claims history starts where tradition has died. The terrain of history studies is where past is not inhabited any longer. (Assmann1991:45)

Heritage interpretation addresses several memories from the sides both of the local community and those of the visitors. This way it can be a practice serving social reconciliations.

2.4. Values, heritage sites and emotions

People in our research found sites and objects more important if they were emotionally engaged and vice versa if sites were generally considered important or famous they tended to demonstrate patriotic feelings related to those sites.

A significant number of emotions seem to be cultural products (Mesquita et al. 2016) The emotions we experience most often are the ones that help us consider ourselves typically good people in the context of our own culture. During a museum visit the quality of experience seems to positively correlate with both positive and negative emotions and negative emotions seem to be in close connection with how useful we think the visit is.

Values do not only correlate with behaviour but also with emotions. Nelissen et al. (2007) found that important values and goals linked to them go together with certain emotions.

Our value system through which we experience the world will influence the emotions we wish to feel. Tamir et al. (2016) found in their cross-cultural survey that self-transcendence, i.e. when one overcomes selfish interests seem to wish for more empathy whereas those who consider self-enhancement a value wanted more the feeling of pride and anger The more important you consider something as a value the more you would like to experience the feelings attached to it and the more you would like to avoid emotions not compatible with them (Tamir et al 2016).

A wide range of emotions are represented on the Russel (1980) circumplex model indicating emotional valence from pleasant to unpleasant and arousal level from calm to agitated (Desmet-Hekkert 2007). We tried to identify that scale and the opposite emotions, where it was possible, in our qualitative research panel as well.

Other our underlining the role of emotions from different aspects: Smith claims all heritage places are the theatre of emotions (Smith 2006).

A shared view of the world may fill our lives with meaning and significance with symbolically helping us overcome our own mortality (Arndt – Vess 2008). Self-esteem is also boosted and maintained by meeting or exceeding the expectations of our group. Several researches prove that people on facing their own mortality will tend to protect their own cultural values, world view, religion or nationality (Greenberg et al 1997, Arndt – Vess 2008)

Positive emotions may have a huge role in the relationship to values and in behaviour. Frederickson’s broaden-and-build theory (1998) claims positive emotions help well-being and adaptation to circumstances by broadening our mental and activity repertoires, increases creativity and the spectrum of attention. Happiness, love, and the feeling of safety motivates discovery and multiplies our intellectual and communal resources.

3. Unesco and international value systems, the system of Hungarian national values

Underlying the idea of World Heritage is the protection of the indivisible heritage of mankind. The first example of this international collaboration was when UNESCO launched a safeguarding campaign in the early 1960s to save Abu Simbel temples. Due to the construction of the Aswan High Dam in Egypt these treasures of the ancient civilisation were in danger of being flooded by the artificially constructed Lake Nasser. Subsequently, the framework of the World Heritage Convention was developed. (Fejérdi 2019)

The UNESCO World Heritage Convention (Paris 1972) aims to preserve the outstanding cultural and natural heritage of mankind. Hungary signed this agreement in 1985 acknowledging the responsibility to protect and preserve the World Heritage sites in its territory for future generations. (Unesco 2019) The spectrum of heritage protection has been expanded with the protection of cultural heritage. The 2003 Paris Convention for the Preservation of the Intangible Cultural Heritage aims to preserve living community practices, mutual recognition of cultural diversity and the expression of intangible cultural heritage. Hungary ratified the convention with the local law „Act XXXVIII. of 2006 on the Proclamation of the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, adopted in Paris on 17 October 2003. The purposes of the Convention are:

- “to safeguard the intangible cultural heritage;

- to ensure respect for the intangible cultural heritage of the communities, groups and individuals concerned;

- to raise awareness at the local, national and international levels of the importance of the intangible cultural heritage, and of ensuring mutual appreciation thereof;

- to provide for international cooperation and assistance.” (Act XXXVIII. of 2006 Article 1.)

Article 15 of the Convention stipulates that the signatory states shall endeavour to involve communities, groups and individuals as widely as possible in the protection of the heritage, and to ensure their active participation in the establishment, preservation and management of the cultural heritage. Along these two international directives, the Act XXX of 2012 concerning Hungarian national values was declared by the Hungarian Government on the 2nd of April 2012.

The concept of Hungarikum – a collective term indicating a value worthy of distinction and highlighting, and which represents the high performance of Hungarian people thanks to its typically Hungarian attribute, uniqueness, specialty and quality – was also incorporated in this law. Three years later, in 2015, the concept was extended to Hungarian values existing outside the country’s borders.

Two well-separable concepts appear in Hungarian legislation. One is the national value. The definition is based on UNESCO directives. This is the basis of the collective concept of the other one, the Hungarikum, which highlights those national values that can be described as “the top performance of Hungarians”. (Act XXX of 2012) The identification and systematization of national values follows the guidelines of UNESCO, therefore in other signatory countries the management of values operates on the basis of a similar methodology and structure. (UNESCO Guide 2017)

In her comparative study, however, Leena Marsio (2014) pointed out that there are also differences in how different countries interpret the convention at the national level. The main difference with regard to the establishment of national inventory is that only a professional group can nominate or, following the spirit of the UNESCO Directive, the proposal is made available to anyone. (Marsio 2014)

The international directives describe well the expectations and several similarities with the Hungarian system can be found.

4. The summary of the research

The empirical investigation about the local values of the Vác, Göd and Fót, and the inhabitants perceptions and emotions, linked to those values, was carried out in 2 major phases: the qualitative research panel was performed in the first line, which was followed by a large-scaled survey of the local population realized during the Spring of 2021.

4.1. Qualitative empirical research: goals, sample, and method

The goal of the qualitative research panel was on the one hand to explore the views of experts (community culture workers and volunteers participating at the local level in the preservation and collection of values) in the field of regional heritage collection, and, on the other, to reveal their local processes of institutionalization and methods they apply to build up collections of local values. We strived to reach that objective with small-scaled in-depth interviews (n=6, we contacted 2 experts from each city) and a focus group discussion. (The focus group discussion was not part originally of the research plan, but it seemed to be necessary to be conducted because we did not receive all the expected answers during the interviewing phase. For example, in relation to the functionality of the local values collection.) The semi-structured expert interviews were recorded at the end of 2020, the focus group interview was carried out in June 2021. All interviews were fixed anonymously and are referenced with single codes preventing any possibility of identification, following the methodology of Babbie (2015).

On the other hand, we wanted to explore the narratives of the local population around the local values: to discover the personal side of the emotional attachment of inhabitants and to have a clear view of those values which are – at the time of the investigation – the most living part of the culture, which are reinforcing the living cities and communities. For that reason, we conducted 27 semi structured interviews (9 persons from each city Fót, Göd and Vác respectively), during the gathering of the sample we used the snowball-sampling method (Babbie, 2015) (using the network of the cultural workers from each city involved in our project). The number of the interviews are not representative, but we strived to have participants with different social and educational background involving men and women in, elder and younger people in equal proportion.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic our interviews - between November and December 2020 - were carried out technically through digital tools (via Microsoft Teams or Zoom conversation) and in a smaller proportion (10% or less) via telephone. We analysed the interviews and the focus group transcript with the method of qualitative content analysis, using the Atlas.ti software.

4.2. Results of the expert interviews and focus group discussion

We identified in the research part carried out with experts (interviews and focus group) 3 different institutional models in the different cities (See table 1.). In fact, the law XXX. of 2012 relating to the creation of National Value System leaves the decision to choose their institutional arrangements of the practical realization (taking into consideration the concept of the subsidiarity) to the local governments of the cities.

In the city of FÓT we can observe a civic solution in this respect: Commission for the Local Values at Fót (FÓTÉB) is made up of six volunteers who are not employees of the municipality. They have two informal leaders, an expert from the culture house leads the group while the other one with a higher education master’s degree in the cultural field supports the members with his methodological knowledge. This commission is very active in communicating with the inhabitants., It operates a Facebook page and edits a quarterly periodical in the topic of the local value collection (Értékőrző Hírlevél in Hungarian). The number of the registered local values in Fót is over a half hundred.

In the city of Göd, we could identify a mixed model: the official decision to enlarge the local value’s list with new elements belongs to the Commission for Culture and Human Affairs a board of three state employee members working for the municipality. This official unit of the local government is seconded by a civic organization of 6 members: this civic team provides the theoretical knowledge necessary for the enlargement. Their members are interested in local history who are mainly retired experts from the cultural sector. Their leader is the director of the local culture house. The preparation (discovery, exploration) and the communication belongs to the civic team whereas the official administration of the list belongs to the group of the local government’s clerks. The mixed model has its advantages, but it is inconvenient that the civic group does not have independent communication channels. The number of the registered local values reaches 72.

In the city of Vác we can observe the municipality model: Most of the tasks related to local value’s collection are done by one of the city’s cultural institutions, the Katona József Municipal Library. There is a historical explanation to this: the city library – a significant collection of registered local values - belongs to the city museum and had already been part of it before the creation of the law 2012. After the new law, most of the old values were taken over to the new list, with a limitation of 75 items. The actual list was finalized in 2017. Today the commission is not so active. The values and their detailed presentation are available on the internet (https://www.vac.hu/vac/ertektar.html) but few people are aware of knowing this list well since it is not communicated intensively in the local media.

Table 1: Institutional model of local value’s collection

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

|

|

City of FÓT |

City of GÖD |

City of VÁC |

|

The model adapted at local level |

Civic model |

Mixed model |

Municipal model |

|

The responsible institutions for the collection of the local values |

Commission for the Local Values at Fót (FÓTÉB) |

The local government’s Commission for Culture and Human Affairs and a civic Commission for the Protection of Value |

The Library Municipal of Katona József, subsidized by the local government |

|

Number of the values in the local heritage collection |

57 recognized local values |

72 recognized local values |

75 recognized local values |

As results of the qualitative content analysis with Atlas.ti software we identified three main functions that the local value’s collection can fulfil: 1. Strengthening the identity and attachment of local inhabitants. 2. Community building of locals. 3. Supporting economic development, based on cultural roots.

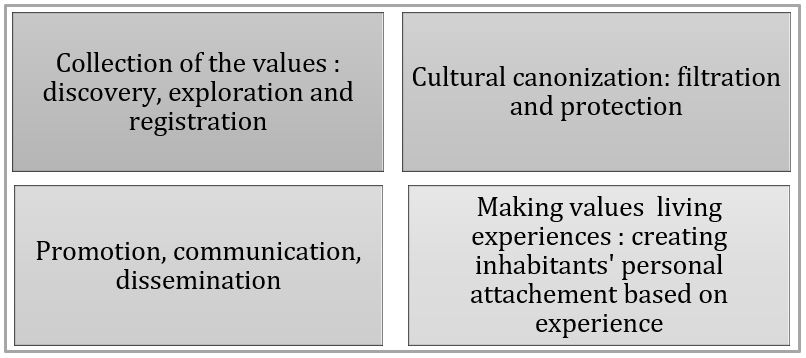

We found 4 major groups of tasks related to the local values collection. Firstly, professionals and volunteers have to collect the values (to discover and explore them) and register them on the official list. Secondly, they need to assure a cultural canonization process: they need to be protective and filter out the values not worthy of the common cultural interest of the community. Thirdly, they need to communicate the values on the list using different channels to reach the local population. Without this dissemination activity many of the values remain unknown for the locals. As a last step, they need to try to keep these values alive by organizing events, festivals or competitions that can bring those values close to the inhabitants through personal experiences (See figure 1).

Figure 1: Professional tasks related local value’s collection

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

The key for success of local value’s collection and the increased attachment of the inhabitants to local values lies in the fulfilment of these 4 groups of tasks. Today, in the investigated cities (for example in Göd and Vác) there are some issues with the intensity of the communication. However, there are many efficient examples in making several local values living in the communities.

4.3. Results of the semi-structured interviews amongst the local population

After the analysis of the interviews with the local population we can conclude that the inhabitants are not aware of the officially registered local values: in the city of Fót, they know almost the half (22 versus registered 57 values), in the cities of Göd and Vác they are aware of approximately 2/3 of the registered local values of the cites. Since people do not have access to the registered list the lack of knowledge may be a result of this fact (see table 2).

Table 2.: Inhabitant’s interviews main results, summary of personal narratives

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

|

|

|

Number of personal local values |

Urban legends |

Historical personalities living in the common knowledge |

Inhabitants’ proposition for the enlargement of local value’s collection |

|

City of Fót |

|

26 local values |

2 stories |

7 persons |

7 propositions |

|

City of Göd |

|

54 local values |

5 stories |

16 persons |

8 propositions |

|

City of Vác |

|

62 local values |

14 stories |

10 persons |

4 propositions |

Although we tried to gather new propositions for the enlargement of the local value lists, few participants came forth with new ideas in that matter. Our research group was successful in identifying several urban legends which are part of the living culture of the local population (depending also on the size, and the historical importance of the investigated cities).

We discovered - having a theoretical background based on the model of Russel’s circumplex model of emotions (cited by Desmet – Hekkert 2007) - different patterns amongst the inhabitants: values made people generally happy and content, but in some minority case we could observe boredom and upsetting as well.

To conclude we can say on the basis of the inhabitants’ interviews that more intensive communication campaigns and the more efficient community cultural actions would be needed in order to turn a wider range of the local heritages into living experiences (This findings are in parallel with Nyaupane –Dallen’s (2009) results.).

5. Summary of the quantitative research

5.1. Research sample

We realized the quantitative research panel with the involvement of inhabitants (n=891) from the 3 cities. In the sample predominantly those residents in whose lives culture plays a more important role were reached, therefore a strong shift towards women and tertiary graduates and middle aged participants in terms of gender, education and age can be observed in all three subsample in the target towns (Fót 200 participants (80,5% female, 19,5% male, tertiary education 56,5%, average age 45,5 years (±11,9), Göd 271 participants (70,5% female, 29,5% male, tertiary education 64,2%, tertiary education 64,2%, average age 51,6 years (± 14,5), Vác 420 participants (76,4% female, 23,6% male, tertiary education 55,7%, average age 42,01 years (±15,2)

The respondents mostly categorized themselves as having a family and most often they have none or one children who is living in the same household (Fót family 70,5%, no child 33,5%, one child 28,5%, Göd family 69%, no child 44%, one child 21%, Vác family 44,8 %, no child 56,2%, one child 19,3 %)

In Fót and Göd most respondents were not born in the given town (Fót 73%, Göd 81%), but moved there a long time ago. In the questionnaire the biggest amount of time the participants could mark was living in the town for more than 31 years (Fót 38%, Göd 39,5%, Vác 38,1%). In the case of Vác, about half of the respondents were born in the town (51.2%)

To the question how much you like to live in this town the respondents gave considerably high scores on a1-7 Likert-scale (Fót 5,08 ±1,58, Göd 5,92 ±1,3, Vác 5,75 ±1,4). There were very few connections or differences among the demographic variables and the “likeability” of the town, although in almost all cases related to the values (familiarity or emotional evaluation) a positive correlation was found between these variables.

5.2. Attendance at public cultural and cultural institutions

Among the public cultural and cultural institutions, the frequency of visits was measured in a selected group of institutions in each town (in Fót 4, in Göd 5 and in Vác 7 commnuity cultural institutions were examined in the survey). The question was focused on the frequency of the participants’ visits before the COVID-19 pandemic.

From the attendance data of public cultural institutions an index of public cultural institution attendance was created in case of Fót which measures the average frequency of visits to these institutions by participants in general. The value of the index in Fót is 1.65 (± 0.88), in Göd it is 1.82 (± 1.02), and in Vác it is 1.97(± 1.35). Although Vác has the highest index the computation of the index does not take into account the number of cultural institutions in the given town, and it is possible that despite the bigger the number of the cultural institutions the average frequency of visits is lower because the visitors couldn’t visit all institutions regularly.

In Fót the Vörösmarty House of Culture was the most visited, with the highest number of regular visitors (11 people). In Göd the data shows that two institutions have regular weekly visitors: the József Attila Culture House (8.1% of respondents) and the Ady Club (4.1% of respondents). In Vác the two most visited public cultural institutions are the Madách Imre Cultural Centre 8% of the respondents (34 people) visiting it on a weekly basis and the Katona József City Library which is visited weekly by 4% of the respondents(17 people).

While in Göd and Vác a significant effect of gender and age was observed on the index, this effect was missing in the case of Fót (age: (r (200) = 0.06, p = 0.39)). In the case of Göd (gender: (t (269) = - 2.026; p <0 .05), age: (r (270) = 0.258; p <0.01) and Vác (gender: (t (401) = -2,180; p = 0.03), age: (r (403) = 0.403; p <0.01), the two bigger towns in the sample women and older respondents were more frequent self-reported users of the cultural institutions, than man and younger respondents. The attendance of public cultural institutions showed a positive and significant relationship by the length of time s/he has been inhabiting the town only in the case of Vác (F (4,398) = 4,308; p = 0.002).

5.3. Statistical results in relation with the highlighted list of local values

In the questionnaire, the examined local values (n=12) were compiled on the basis of the values included in the list of the local depository (values already included in the Municipal Depository of the given town or planned to be included in those) and the values identified in the interviews of the qualitative research phase.

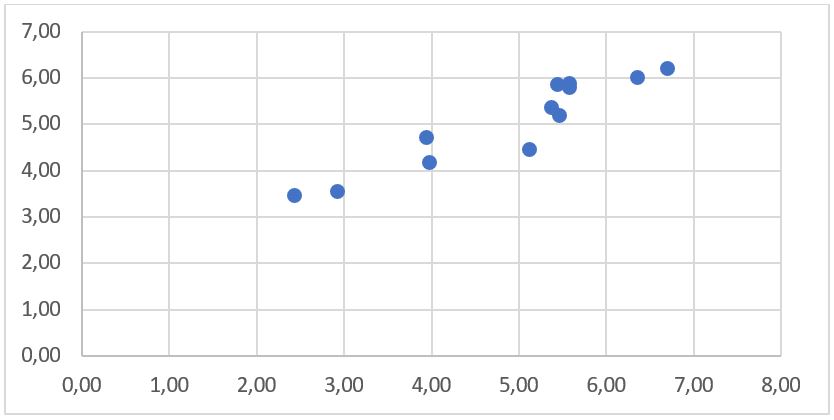

Based on the familiarity and positive attitude the 12 values of Fót could be divided into four groups (see figure 2). The values in the first group can be described as well-known values evaluated with remarkably positive attitude (Hungarian Trifle -in Hungarian the Somlói galuska - and Lake Somlyó). Regarding the Hungarian Trifle, the question arose as to how much it can be considered exclusively as a value of Fót and if this outstanding positive evaluation can also be attributed to the nature of the food in question, being a popular dessert. Lake Somlyó leads the list of values as an outstanding natural value.

In the next group, the positive attitude towards the values is high, but not the highest (the averages ranging from 5.21 to 5.89) (Károlyi Castle and Park, Somlyó Mountain, Fáy Press House, Church of the Immaculate Conception and the Clove Tomato of Fót) and the familiarity with these values is also relatively high (with averages ranging from 5.37 to 5.58). It is worth noting, that several types of values were included in this group (e.g., built heritage, natural value, and agricultural value). The Clove Tomato of Fót as a value unexpectedly occupies such a prominent place, which may be due to the fact that an article about the Clove Tomato of Fót was published twice in the local newspaper last year. This result might show that in the medium-term the news and reports dealing with values in the local media might have an impact on the evaluation of these values.

The third group included the three values with medium scores both in familiarity and positive attitude (Festival of Autumn, Károlyi Hussars and Spring Campaign and the Németh Kálmán Memorial House and Garden). Finally, in the fourth group two values were classified as being characterized by low familiarity presumably because of the relatively low positive attitudes (Suum Cuique colony and choirs of Fót).

Figure 2: Local values of Fót on Familiarity (X axis) – Emotions (Y axis) diagram

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

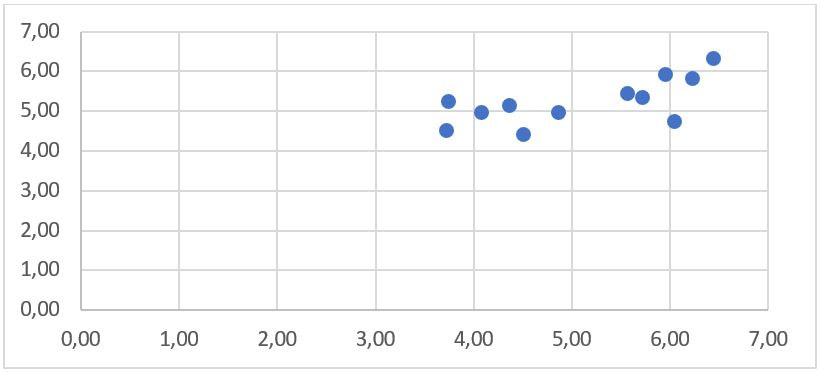

Using the same method as in the case of Fót categorizing the 12 values of Göd based on the familiarity and positive attitude two major groups could be found (see figure 3). Each group consist of six values. The first group contains the more well known and more positively evaluated six values (average familiarity ranging from 5.56 to 6.44, average positive attitude ranging from 5.25 to 6.34), all of them being natural environmental values (Danube bank at Göd, Cycling path at the Danube, Thermal water and thermal bath in Göd, Sand island and floodplain forest, Kincsem racehorse and the related stables, bog of Göd and the golf course)

The second group of values included a more varied group of values (e.g. natural and built heritage, a festival, and even achievements of a sport club) (Szakáts-garden, Chocolate Roll Festival, Huzella – garden, Kayak-canoe division of Göd Sport Club, Villas of Göd, Volunteer Fire Station Memorial Site) with slightly lower familiarity and positive attitude scores (average familiarity ranging from 3,71 to 4.85, average positive attitude ranging from 4.42 to 5.14). Both groups can be found in the upper right quarter of the familiarity-emotion diagram meaning that even though a distinction could be done among the values, all of them are relatively highly evaluated in both familiarity and in regard of positive attitude, too.

Figure 3: Local values of Göd on Familiarity (X axis) – Emotions (Y axis) diagram

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

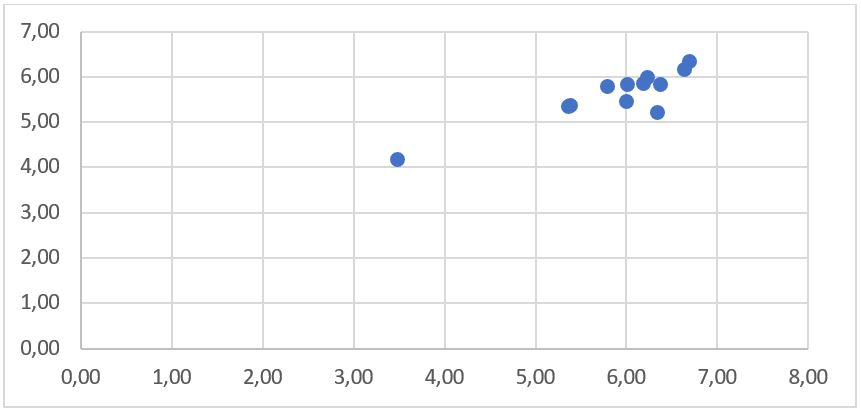

The 12 values of Vác based on the familiarity and positive attitude mostly form one big group with one value being an outsider (see figure 4). The outsider value is the Rowing Club of Vác and its achievements (average familiarity 3.47, average positive attitude 4.18). It is worth noticing the difference in the evaluation if the two sports clubs are included in the research. While in Göd the kayak-canoe division was in the lower rated group, yet it was not an outsider and had somewhat higher ratings than the rowing club in Vác. One potential explanation of this slight difference might lay in the overall appreciation of the two sports in Hungarian culture, traditionally - unlike rowing - kayak-canoe being one of the successful sports for Hungarian contestant in world sport events.

All the other values of Vác (Danube bank, Triumphal arch, Stone saints bridge (Kőszentes híd), Worldly Fair of Vác, Grove, Seven Chapel Shrine, Church of the Whites, Baroque downtown, Cycle path at the Danube, Monument of Independence’s War, Bishop’s Palace) have very similar scores both in familiarity (average ranging from 5.38 to 6.69), and positive attitude (average ranging from 5.22 to 6.34), with the Danube bank and Triumphal arch having slightly higher ratings among the other values.

Figure 4: Local values of Vác on Familiarity (X axis) – Emotions (Y axis) diagram

(Source: own compilation based on the research results)

5.4. Conclusions

The questionnaire was completed by participants in the spring of 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the instruction stated that the respondents should not comment on their current but on their pre-epidemic visitation habits several responses conveyed a memory bias in the self-reported frequency of visits both in terms of attendance at public cultural institutions and when asked about recharging sites. Respondents evidently are temporarily having difficulties imagining themselves in a non-COVID situation, and outdoor venues have an advantage over enclosed spaces.

Of the three towns, Vác is the most significant monument site. This feature of the city seems to be important to the residents and they are conscious of this heritage. Heritage sites received high scores on the familiarity scale, and although the evaluation is somewhat lower than the familiarity, it is still high, and these two measured features of the values involved in the questionnaire do not show much difference from each other.

Based on the respondents' comments, the category of “heritage protection” was added among the urban phenomena influencing the reception of local values in all three cities, as several people expressed their concern about the deterioration of the values of the town. In the case of Fót and Göd the protection was stressed more about natural environmental values, while in Vác the emphasis was more on the built heritage and built values. In the city of Vác living in a historic city is essential for many to have a positive attitude to where residents live.

A reoccurring phenomenon in the results that positively evaluated places can be named as places of neglect (e.g. the Grove in Vác), that might seem contradictory. The fact that the current state of these places is considered neglected and discredited and respondents want to see the value more beautiful is not really the opposite of being positively evaluated and loved. As the familiarity was also related to how much one likes to live in his town, it is conceivable that the respondents’ attitude towards the city as a whole has been extended to the given value as well.

Based on the qualitative answers collected in the questionnaire Maslow’s hierarchy of needs can be implemented. Especially emphasized in the case of Fót, it was observed that while public safety and infrastructural issues (e.g. dirt in the vicinity of renovated monuments, homeless people, muddy roads) are very important problems in the life of the town, these problems act as obstacles to paying attention, to accepting and to appreciating the values of the town, sometimes even make it impossible. It is more difficult for the population to pay attention to the protection of values-such problems may certainly make heritage protection a secondary or tertiary need in residents’ life.

Summary

Values, emotions, memory, cultural memory, and heritage in terms of self-identification and self-esteem are categories worth examining in any cross section of time and space in the framework of the latest theories. Concepts and ideas that seem to have always been with us may gain new profiles of interpretation in the light of new theories and especially with the help of bringing those theories into play together. Theories can mutually fertilize each other when making them confront on an interdisciplinary stage. Phenomena we have had impressions about may reveal new depths and spectra when examined in interdisciplinary interrelations.

To investigate reactions of citizens to their hometown and their appreciation of traditional values around them is of utmost importance. Locals, visitors, and professionals of interpretative guiding meet in the arena called authenticity, and imaginative space highly determined by values, memory, and emotions.

Our research was serving this goal, in a more narrow space of the cultural heritage: examining the local values of three middle sized Hungarian cities in Pest county (Fót, Göd and Vác), and giving an important feedback on the functions and models of local values depositories, and on the other hand on the emotions and awareness of inhabitants in relation to their local values and heritage.

References:

- Act number XXX of 2012 concerning Hungarian national values and Hungarikums (2012. évi XXX. törvény a magyar nemzeti értékekről és a hungarikumokról).

- Andorka, Rudolf (2006): Bevezetés a szociológiába (Introduction to sociology). Osiris kiadó

- Arndt, Jamie – Vess, Matthew (2008): Tales from existential oceans: terror management theory and how the awareness of our mortality affects us all. In: Social and Personal Psychology Compass, 2/2, 909-928 p.

- Assmann, Jan (1992): Das Kulturelle Gedächtnis.Schrift,Erinnerung und politische Identität in frühen Hochkulturen. Verlag C.H.Beck, München

- Babbie, Earl (2015): The Practice of Social Research. Cengage Learning editor,14th edition, p. 591.

- Bábosik, Zoltán (2001): Értékközvetítés napjainkban (Value transfer nowadays). In: Új Pedagógiaia Szemle, 2001/12. 3-10. Available: https://ofi.oh.gov.hu/tudastar/ertekkozvetites (Accessed: 02. 01. 2021)

- Elias, Norbert (2004): A civilizáció folyamata (Process of the civilisation). Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest.

- Bagnall, Gaynor (2003): Performance and performativity at heritage sites. In: Museum and Society, 1/2, 87-103. p.

- Bardi, Anat – Schwartz, Shalom (2003): Values and behavior: strenght and structure of relations. In: Personality and Socialpsychology Bullettin, 29/10, 1207–1220.

- Campbell, Sue (2006): Our faithfulness to the past: reconstructing memory value. In: Philosophical Psychology, 19 /3, 361-380. p.

- Desmet, Pieter – Hekkert, Paul (2007): Framework of Product Experience. In: International Journal of Design, 1/1, 13-23. p.

- Giddens, Anthony (1995): Szociológia (Sociology). Osiris Kiadó, Budapest

- Grad-Gyenge, Anikó – Kiss, Zoltán – Károly – Legeza, Dénes – Pontos, Patrik – Tomori, Pál (2018): A nemzeti kultúra és a nemzeti kulturális tartalom jogi definiálása – különös tekintettel a szerzői jogi és egyéb kulturális szabályozási kapcsolódási pontokra. In: Iparjogvédelmi és Szerzői Jogi Szemle, 13/5, 7-32.

- Greenberg, Jeff - Solomon, Sheldon - Pyszczynski, Tom. (1986): Terror Management Theory of Self-Esteem and Cultural Worldviews: Empirical Assessments and Conceptual Refinements. In: Advances in Experimental Social Pscychology, Vol 29, 1997, Pages 61-139.

- Halbwachs, Maurice. (1941): La Topographie Legendaire des Evangiles en Terre Sainte. PUF, Paris.

- Hankiss, Elemér (1977): Érték és társadalom. Mit tartunk majd igaznak, jónak és szépnek 2000-ben. (Value and society – What we will held for good and beautifoul in 2000) Magvető Kiadó, Budapest.

- H. Farkas, Julianna (2006): Értékek, célok, iskolák (Values, goals and schools). Balassi Kiadó, Budapest.

- Fejérdy, Tamás (2019): A Világörökség mint kulturális örökségi laboratórium (World heritage as laboratory of cultural heritage). In: Korall, vol. 75, 22-45. p.

- Fredrickson, Barbara L. (1998): What good are positive emotions? In: Review of General Psychology, 2/3, 300–319. p.

- Lorand, Ferenc (2002): Értékek és generációk (Values and generations), OKKER Kiadó, Budapest.

- Marsio, Leena (2015): Intangible Cultural Heritage. Examples of the implementation of the UNESCO 2003 Convention. Available: https://www.cupore.fi/en/publications/cupore-s-publications/intangible-cultural-heritage-examples-of-the-implementation-of-the-unesco-2003-convention-in-selected-countries-under-comparison-report-summary-and-conclusions (Accessed: 10. 12. 2020)

- Mayer, John D. – Salovey, Peter – Caruso, David R. (2008): Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? In: American Psychologist, 63/6, 503-517. p.

- Morton, Adam (2013): Emotion and imagination. Cambridge, Polity Press, 230. p.

- Nelissen, Robert M. A. – Dijker, Anton J. M. –De Vries, Nanne (2007): Emotions and goals: Assessing relations between values and emotions. In: Cognition and Emotion, 21/4, 902-911. p.

- Nyaupane, Gyan. P. – Timothy, Dallen. J. (2009): Heritage awareness and appreciation among community residents: perspectives from Arizona. In: International Journal of Heritage Studies, 16/3, 225-239. p.

- Russell, James (1980): A circumplex model of affect. In: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39/6, 1161-1178. p.

- Smith, Laurajane (2014): Visitor Emotion, Affect and Registers of Engagement at Museums and Heritage Sites. In: Conservational Science in Cultural Heritage, 14/2, 125-132.

- Smith, Laurajane – Campbell, Gary (2015): The elephant in the room: Heritage, affect and emotion. In: Logan William (ed) – Craith, MÃiréad Nic (ed) –Kockel, Ullrich (ed) (2015): A Companion to Heritage Studies. Wiley-Balckwell, 624. p.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. – Sagiv, Lilach (1995): Identifying culture-specifics in the content and structure of values. In: Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26/1, 92-116. p.

- Sevcenko, Liz (2002): Activating the past for civic action: the international coalition of historic site museums of conscience. In: The George Wright Forum, 19/4, 55–64. p.

- Tamir, Maya – Schwartz, Shalom – Vishkin, Allon et al. (2016): Desired emotions across cultures: A value-based account. In: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111/1, 67–82. p.

- Tóth, István György (2009): Bizalomhiány, normazavarok, igazságtalanságérzet és paternalizmus a magyar társadalom értékszerkezetében (Trustlessness, lack of norms, injustice and paternalism in the value structure of the Hungarian society). TÁRKI, Budapest.

- UNESCO (2019): Guidance note for inventoring intangible cultural heritage. Available: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/46568-EN.pdf (Accessed: 10. 12. 2020)

- Vitányi, Iván (2006): A magyar kultúra esélyei (Chances for the Hungarian culture). MTA Társadalomkutató Központ, Budapest.

- Wells, Marcella – Butler, Barbara H. – Koke, Judith (2013): Interpretative planning for museums: integrating visitor perspectives in decision making. Routledge, Walnut Creek, California.

- Wertsch, James (2002): Voices of collective remembering. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.