Mihály Róbert Drabancz – Mihály Fónai: Intellectualism, educators and the regime change

DOI szám: https://doi.org/10.64606/ksz.2025203Cikk letöltése: pdf

2025-12-22

Absztrakt: Tanulmányunkban a népművelőknek a rendszerváltáskori szakmai állapotával és a változó társadalmi valóságban betöltött szerepével foglalkozunk. E témában számos írás megjelent, ezért elsősorban arra fókuszálunk, hogy a közművelődés szereplői játszhattak-e szerepet a rendszerváltás politikai, társadalmi, illetve kulturális változásaiban. Az értelmiségnek, és különösen az értelmiségi elitnek a rendszerváltásban játszott szerepét a szakirodalom alaposan feltárta, a kilencvenes évek „tranzitológiai” írásai, valamint a korszak elitkutatásai alapvetően erről szóltak (Fónai, 1995, 2003; Kristóf, 2011). A szakirodalomban gyakran utalnak arra, hogy a rendszerváltáshoz vezető folyamatok, jelenségek kapcsolatba hozhatók a népművelés, majd a közművelődés funkcióváltozásaival is, hiszen a művelődési otthonok a nyolcvanas évek változásai során helyet adtak az új civil, gyakran ellenzéki, kezdeményezéseknek. Ezt az állítást nehéz igazolni, a tanulmányban arra törekszünk, hogy a folyamat implicit és explicit jellemzőit ragadjuk meg. Ez leginkább a népművelés/közművelődés változásaiban és az intézményrendszer működésében írható le. Mivel a népművelés, közművelődés megítélésünk szerint általánosabb értelmiségi funkciókat, szerepeket „professzionalizált”, mindenképpen foglalkoznunk az értelmiség fogalmával és szerepeivel is, valamint bemutatjuk azokat a szakmai vitákat, valamint kutatásokat, melyek pontos képet adnak a szakma állapotáról a rendszerváltás pillanatában.

Abstract: In our study we deal with the professional status of the popular educators at the time of the regime change and their role in the changing social reality. A number of papers have been published on this topic, so we focus on the role that the actors of public culture may have played in the political, social and cultural changes of the regime change. The role of intellectuals, and especially of the intellectual elite in the regime change has been thoroughly explored in the literature, and the “transitological” writings of the 1990s and the elite research of the period were basically about this (Fónai, 1995, 2003; Kristóf, 2011). In the literature, it is often referred to the fact that the processes and phenomena leading to the change of regime can be linked to the changes in the functions of popular education and then of public education, since during the changes of the 1980s, the cultural centres gave place to new civil, often oppositional, initiatives. This claim is difficult to prove, and in this paper, we aim to capture the implicit and explicit features of the process. This can best be described in terms of changes in popular education/public education and the functioning of the institutional system. Since we believe that popular education and public education have “professionalised” more general intellectual functions and roles, we will also deal with the concept and roles of intellectuals, and present the professional debates and research that give an accurate picture of the state of the profession at the time of the regime change.

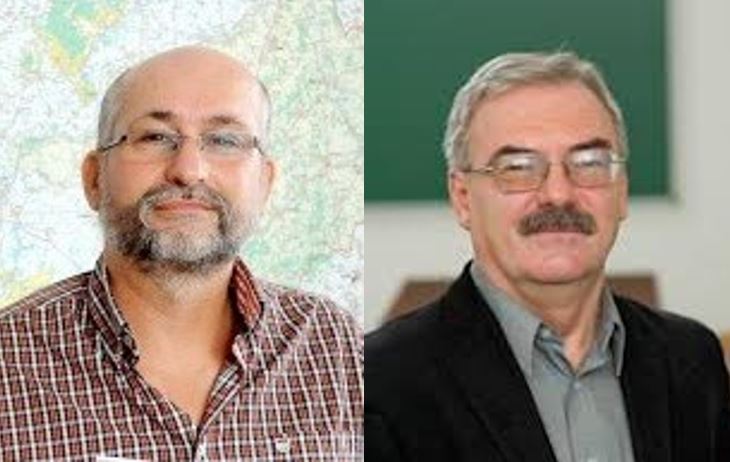

Drabancz Mihály Róbert: Tokaj-Hegyalja Egyetem

Fónai Mihály: Debreceni Egyetem

The concept of intellectualism

In the literature on intellectuals, there is no generally accepted definition of “what is intellectualism” or “who is an intellectual”. There are a number of possible reasons for this, such as historical changes in the shape, function and regional types of intellectualism, which will certainly influence the answer to this question. Definitions of intellectuals and self-definitions of intellectuals typically emphasise some function, historical or structural characteristic of intellectualism (Fónai 2008). Intellectualism theories can be divided into two broad categories, depending on their focus. One group includes those that focus on the functions and roles of intellectuals, while the other group focuses on the social structure and history of intellectuals. It further modifies the situation if we also want to talk about the self-image of intellectuals and the external image and expectations of intellectuals when defining intellectuals (Fónai, 1988).

The path of the three basic historical types of intellectuals diverged from the 18th to the 19th century (Fónai, 1992; 1997; 2003). The categories of professionals, such as doctors, lawyers, engineers, while described in terms of their functions in society through their professions, seem to paradoxically now also carry orderly traits. This can be explained by the fact that the earliest professionalised groups, whose work was most specialised and for which there was a specific social demand, became independent within the framework of the orderly society, and this influenced their later habitus and professional organisation.

The emergence of the other major historical type of intellectuals, the intellectual, is dated in some literature to the period before the French Revolution and partly to the Enlightenment (Im Hof, 1995). Part of the characteristics of the intellectual as a type also emerged at this time: intellectuals emerged as the intellectual and moral elite of the intellectuals, and also accepted themselves as such. Later intellectuals claimed for themselves a role of social critique, the task of revolutionary change and a commitment to the new in general. Its representatives were philosophers, social thinkers and artists. The third historical type of intellectuals, the intelligentsia, emerged in Eastern Europe (Seton-Watson, 1970). In many ways, it resembles the intellectual – for example, in its openness to social problems – but there are more differences than similarities between these two types of intellectuals. The explanation lies in the societies in which intelligentsia was created. These societies have a dual and congested structure, with little or no bourgeoisie. Intelligentsia conceptualised the transformative role of modernisation and its leadership as a mission for itself. Its aim was to change the existing system and/or to achieve national independence, which it hoped to achieve through its own leadership.

There are also specific roles associated with these historical types of intellectuals. General intellectual roles (and functions), the emergence of which is linked to the non-concept of intellectuality; these roles (and functions) historically predate the emergence of the types of European intellectuals that have developed over the last two centuries. These include the roles associated with the creation of ideas and culture, as well as the roles of “innovator” and “creator”. The roles associated with intelligentsia as a type of intellectual, which are represented in the form of the “vates and the missionary”. The roles associated with the intellectual as a type of intellectual: the “living conscience” and the “anti-political” characters become dominant roles. The roles associated with professionals as a type of intellectual: these are the roles of “expert – designer – technocrat”.

The role set of the “social critic” applies to all three types of intellectuals, but there is a significant difference between them, despite the social criticism. The role of the intellectual as a social critic is characterised by a contemplative attitude and an outsider stance, which is why this role has been seriously attacked and questioned from the beginning. The social-critical role of intelligentsia is much more “activist” and concrete, while the intellectual formulates his critique in the name of generally abstract goals and principles, intelligentsia always acts on behalf of some community or social group, representing its interests, becoming an “activist critic”. Professionals treat social criticism itself as a professional issue, formulating their “technocratic”, “expert” critique on the basis of the criteria of a particular profession.

Most of the writings and studies on intellectualism deal with theoretical issues, with little empirical research on, for example, the roles of intellectuals, their self-image and identity. The vast majority of research in Hungary took place in the 1970s and 1980s, and after the regime change, although intellectuals (including the elite) were of great importance, there was hardly any empirical research. Once again, it should be emphasized that post-regime change empirical research on intellectuals in Hungary is strongly intertwined with research on elites, especially cultural elites (Kristóf, 2014; Szalai, 1996). Among the few empirical studies of the 1980s, the research of Mihály Fónai (Fónai, 1986; 1990/a; 1994; 1997) is worth mentioning. In 1987, a comparative survey of intellectuals and non-intellectuals was carried out in Ibrány. The two groups have significantly different views and expectations of intellectuals in terms of their social tasks and roles. In the self-definition of intellectuals, being an intellectual and the nature of the work they do dominate (rank 2-3, 15.2-15.2%), while the role of education is less important (rank 4, 10.8%). In contrast, the perception and image of intellectuals by non-intellectuals is determined by their education and the nature of the work they do. This group attaches marginal importance to “being an intellectual” (0.9%). The self-image and articulation efforts of intellectuals are greatly influenced by the expected or assumed forms of behaviour, qualities, personality traits and activities that result from “being an intellectual”. The majority of the non-intellectuals interpret literacy as a distinguishing feature, and see it as an explanation for the closed, “elitist” nature of intellectuals (Fónai, 1988: 97-98).

In the two-century history of Hungarian intellectuals, the most controversial issue has been public engagement and setting an example. In the late 1980s, there was no difference between intellectuals and non-intellectuals in the perception of public engagement, meaning that intellectuals were “expected” to engage in public life, which they accepted – but this engagement was not public life influenced by the interests and needs of “local society”, but rather by the traditional and partly paternalistic, formal “public life-social work” perception.

In the year of the regime change, a survey was conducted among Nyíregyháza college students on their perceptions and expectations of intellectuals, for example, regarding the intellectual lifestyle and the social roles of intellectuals (Fónai, 1990/b). Based on the student responses, the following lifestyle types were identified: culture-centred, self-education-and-self-development-centred, over-stressed-stressed-and-self-destructive, open-creative-innovative, critical-public, profession-centred. The students’ image of intellectuals was very much in line with Fónai’s research during the period of regime change. Students also highlighted the intellectual leadership role of intellectuals (42.1%), as well as the creation, transmission and valorisation of culture (22.3%), and less important were the role of example and responsibility (13%), and the public, critical and problem-solving roles (6.5%).

Among the results of the 1991 research in Nyíregyháza (which was carried out in intellectual and non-intellectual samples), we highlight the results concerning the relationship between intellectuals and elites (Fónai, 1994; 1997). It is very instructive to see who was considered elite around the time of the regime change, and what they thought about how to get into the elite. Who were regarded as the elite: politician, economic leader, scientist, artist, doctor, engineer, university professor, by the intellectuals; and doctor, economic leader, politician, artist, scientist, engineer, agricultural engineer by the non-intellectuals. Who were classified into the elite of intellectuals, by the intellectuals: scientist, politician, business leader, doctor, artist, university professor; by the non-intellectuals: doctor, business leader, politician, artist, engineer, university professor. What is striking is that there was not really much difference between the elite image of intellectuals and non-intellectuals, and no distinction was made between the elite and the elite of the intellectuals – this may have been due to the fact that the different elite groups were changing at the time, and the structural disintegration and disempowerment of the intellectuals had not yet taken place. As regards the way of entering the (intellectual) elite (and the characteristics of the intellectual elite), both groups have in common the emphasis on material wealth and on education and knowledge. There is a difference in the perception of cultural creation and transmission, and in the perception of interweaving, the former being seen as more important by intellectuals and the latter by non-intellectuals.

From folklore to popular education

Throughout the two centuries of national history of popular education/public education, different concepts have been used to describe the field. Two things, or a number of components, can be distinguished. One is the content of what we mean by the concept of folklore, and the other is the institutional system and the actors involved in its implementation. Of particular relevance to our topic is the question of when and to what extent the changing popular education/public education – not ignoring political, ideological, cultural and economic changes – was in a position to play a role in the process of regime change, despite its relative autonomy.

During the decades of Hungarian state socialism, two concepts of popular education, their respective goals, tasks and institutions emerged: popular education (although the term itself was used earlier, its institutional system and goals differed significantly, especially from the popular education of the 1950s, but also from that of the 1960s) and public education. By the mid-1960s, the “Soviet-type cultural mediation” (Ponyi, 2023), including popular education, was in crisis, and the response was public education, which was still a period of “strictly controlled education” (see the principle and practice of 3T), but the concept of self-activity had already appeared in the vocabulary and legislation. Notwithstanding the economic, political and cultural crises of the 1970s, a process of reform in the field of public education was launched, characterised by greater openness and a community approach. Public education and its professional institutions, cultural centres, but also other social and cultural actors, have significantly expanded the institutional, organisational and content boundaries of culture and public education. As Ponyi formulates it in his study: “One of the most important characteristics of the period is that, in addition to institutional public educational activities, which were institution-centered, in line with political expectations and could already be called traditional, innovative professional activities appeared, which had previously been forbidden or tolerated, such as entrepreneurial-type, needs-based fulfilment of tasks, mental health specialisation, socio-cultural animation, community and village development, folk culture and the cultivation of traditions, which was a direct result of the dance-hall movement of the 1970s, the renewed strengthening of adult education, the increase in the number of non-profit associations and their cultural, political and public activity, the revival of the folk college movement, the emergence of alternative and opposition movements and the expansion of cooperation with them.” (Ponyi, 2023: 123-124)

As we have pointed out, by the end of the sixties, the top-down and over-politicised popular education was in serious crisis, and the response was public education. The state party (MSZMP) involved representatives of the cultural professions in the development of the concept of public culture, which led to the “socialisation” of the field in the mid-seventies. The concept itself was a multi-stakeholder, multi-channel funding model, with the resulting mechanisms breaking down the constraints imposed by politics. The economic crisis at the beginning of the 1980s and the responses to it legalised market processes, also in the field of culture. This has also strengthened the socialisation of public education, contributing to the spread of the concept and practice of “bottom-up culture”. A sign of this was the club movement, the amateur art movement, the various associations and societies. In the medium term, the main winner in public education has been the network of cultural centres. This process also contributed to the fact that by the mid-1980s, cultural centres had become the arena for various reform experiments (Drabancz – Fónai, 2005: 224-228). As a result, by the end of the 1980s, cultural centres focused on entertainment and public courses but also functioned as “community spaces”, hosting civic initiatives, often critical of the system. This model collapsed during the change of regime, partly because of its contrived nature (a real cultural market was created and civil initiatives were allowed to operate “in their own right”). This is well illustrated by the data of the cultural centre network of Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg county (Fónai, 1998). On the one hand, there has been a slow decline in the number of cultural centres (177 in 1993, 155 in 1995, 141 in 1995). In the eighties, the “creative communities” were one of the directions of reform, with 370-380 in the county, but their number had fallen by a third by the early nineties, and a similar process was taking place in the number of members of the creative communities (in 1988, there were 7644 members of the creative communities). One of the successful market reforms of the 1980s was in the area of language teaching, with the majority of language courses being organised by the cultural centres, and the number of language courses and the number of participants falling by a third by the early 1990s. The change was smaller for art and other courses (Fónai, 1998: 52-53). We can say that the cultural centre network, which had considerable autonomy in the eighties, was an institutional framework of “community activity” alongside “market aspects”, within which the processes and forms of activity that prepared and supported the regime change actually appeared. In the following, we illustrate the role of popular education/public education and popular educators in the processes leading to regime change through the results of some empirical research.

Few empirical studies have examined the actual, practical, substantive functioning of popular education and the operation of cultural centres. It was more common from the 1960s and 1970s onwards for researchers to draw conclusions based on the analysis of official cultural statistical surveys, e.g. on the structure of activities in cultural centres. Nowadays, in addition to the analysis of statistical data, studies based on data collection have also become widespread (Koncz, 2002; Ponyi et al., 2019).

László Boros (2017) analyses the youth movement of the eighties and writes about the role of popular educators and cultural centres. Boros presents several forms of (bottom-up, spontaneous) youth movements. Spontaneous marginal organisations included underground groups, vagrancy, drugs and delinquency groups, which were not linked to institutions, including community centres. Non-marginalised spontaneous youth organisations also emerged, these were voluntary, organised communities and often received support from various institutions. As Boros writes: “Particularly important were those working in public educational institutions, who gave young people a place to meet in community centres, factory youth clubs, library auditoriums and educational establishments, to a certain extent legalising their gatherings. In some cases, they have integrated them into the programme of their institution, hiding behind somewhat “masking” names, and helped to invite external speakers. Most of the people who gave help had a degree in popular education, often came into conflict with the official apparatus in their own work, and learned to find the cracks in the system’s crumbling walls.” (Boros, 2017: 8).

In a similar way, public educators and cultural centres could support young intellectuals’ organisations, partly by providing space for them and partly by organising lectures and discussion evenings. The higher education (youth) movements were primarily linked to universities, although this did not mean the active involvement of universities, but the boundaries were quite elastic, suffice it to refer to the professional colleges. The thematic spontaneous youth groups (environmentalists, organisers of alternative peace movements) could also be linked to the cultural centres, but in this case, too, the institutions provided a space for these organisations. It seems that in the eighties, the cultural centres could contribute to the reform processes in two areas, including the pushing of the boundaries of the system (by implication, the regime change), one of which is that the institutions provided a “home, a venue” for organisations, programmes and individuals that, in the former terminology of the state party and its cultural policy practices, belonged to the “tolerated” or sometimes “forbidden” category. This is one sign of the inertia of (educational) politics. The other way was when community centres not only hosted programmes and organisations, but inspired and generated them themselves.

Changes in the profession and training

The training of popular educators as professionals is closely linked to the history of popular education in Hungary. The history of popular education shows that from the very beginning it has been shaped by the “cultural policy” of the state, including the training of professionals, the legal and economic conditions for the development of the institutional system and the content of the activity. Alongside state education policy, other actors have played a role, with varying degrees of intensity and opportunity, and there have even been periods when non-state actors have been the dominant influence on education. The name given to the “popular culture”, the activity and the specialist of each period is also revealing, telling us a lot about the general and cultural policy of the period, as well as about the social history of the period. From this point of view, the title of Tamás T. Kiss’s (2000) book is apt, as he reviews the history of training and the profession from “popular educator” to cultural manager.

As a result, the ideal professional has always been different: the organiser in the age of liberal education, the propagandist in the fifties, the educator in the sixties, the teacher as the model or the main characteristic of the professional. According to T. Molnár, from the seventies onwards, a new role began to emerge within the profession, namely that of developer. The 1990s saw the emergence of cultural organiser, cultural manager, adult educator, cultural service provider, leading not only to a multiplicity of names but also to a further fragmentation of the previously somewhat unified (albeit constructed) profession (see also: Fónai, 1991; Mankó, 1990). In the last decade, the profession and name of andragogist has become more widespread, which has also meant the renewal and differentiation of the field (T. Molnár, 2016). The “content” and designation of the profession and training is heavily influenced by politics, partly on the starting and designation of training (e.g. in 1974), but also on its termination or change.

Mária Mankó (1991) notes that the months of regime change were months of uncertainty for both the profession and training, as the abolition of training and the dismantling of the established institutional system were discussed, which had a serious impact on the self-image of professionals – it was typical that the “public educational politics” made its views known. Surprisingly, training institutions have been more proactive in responding to the situation, as the profession has begun to become reorganised. At that time, the new name of the profession and the college degree, “cultural organiser” (in university education “cultural manager” (Fónai, 1991; T. Kiss, 2000) was adopted by the ministry’s management. In the 1990s, higher education in the field developed specialised courses in cultural management (e.g. animator, mass communicator, cultural manager), which was also a reaction to the new situation. This also contributed to the consolidation of the new profession or professions (cultural organiser, cultural manager) until the mid-twenties.

Popular education and popular educators in research

Regardless of changes in its name and professional content, the profession of popular education started to professionalise in the 1960s (Kleisz, 2005). The profession required the establishment and operation of a consensual professional content, higher education training, and a professional organisation, completed in the 1970s. This does not mean that there have not been disputes, in particular regarding the professional content and the related purpose of the training and the knowledge and competences transferred. It seems to be a peculiarity of the “popular educator” profession that until the end of the eighties it was in a constant state of flux due to the often changing professional goals and contents, the structural and funding problems of the institutional system, and the political influence. Due to external influences (and this applies also to the first half of the twentieth century), popular education can be considered a “constructed” profession (Fónai, 1990, 1991; Mankó, 1991), which is strongly influenced by changes in external conditions. One only has to think of the changes in professional titles: folk educator, folk teacher, popular educator, cultural organiser, cultural manager, andragogue, community organiser – it seems that not only popular education is a “constructed” profession, but also its predecessors and “successors”, and this is a major threat to the status of these professions. (Etzioni, 1969; Haug, 1973).

Teréz Kleisz (2005) examined the history of popular education professions within the framework of professional theory. It traces the history of the development of the profession back to the reform era (folk education), and presents in detail the situation, content, institutional system and actors of popular education in each period, including the popular educators themselves. As indicated, the names of those involved have changed a lot over the decades. In order to talk about “professions”, it was necessary to define the professional content of the profession and also (higher) education. The “politics-dependent profession building” took place after 1948. In the 1960s and 1970s, when the profile of the profession was being shaped, the discourse on the profession was characterised by the dichotomies of science versus professional practice, science versus craft, in which politics was also strongly involved, supporting the second option (which is why, for example, university education was under constant threat). In educational institutions, the scientific background was dominated by pedagogical, then andragogical and sociological approaches (Drabancz, 2008). The state of the profession is well illustrated by the leading cultural researchers of the period: the popular educator as a developer of culture (Andor Maróti), the popular educator as a planner of culture and researcher of culture (Sándor Heleszta), the popular educator as a purposeful educator (Mátyás Durkó). Equally divisive was whether institutional, state-driven or “bottom-up” community life should shape popular education and, in this context, the profession. Politics has been less supportive of the second option, although it has made steady concessions in this direction as the regime’s position has deteriorated. In the 1990s, the above complex expectations of professional content were replaced by new ones, which led to a divergence of the popular educator profession. (Drabancz - Mihály Fónai, 2005; T. Kiss - Tibori, 2015).

The “profession” of public education, the popular educationist, resistant to so many name changes, is, in its recent form, essentially a constructed profession; a profession artificially created by the demands of a particular era, burdened with ideological tasks. During the few decades of its history, the profession underwent enormous internal struggles, and it was only in the 1980s that it acquired its definitive professional content: it was then that its internal division of labour was established and it became accepted as a profession in society. Its tumultuous fate was marked year after year by renewed professional debates and intentions for change, which showed that this career, profession, occupation, despite all its contrivedness, also has a real social function and community tasks. What is more characteristic of its contradictory nature is the fact that it was both “party-state” and oppositional. (Fónai, 1991: 3-4)

Several empirical studies were carried out among popular educators and, in the 1990s, among cultural organisers and students of popular education. These tell us a lot about the state of popular education/public education and the profession. In the present framework, we will refrain from analysing the comprehensive research of the eighties, it would lead too far, suffice to refer here to the studies on the situation of public education that started in 1986 in the framework of the National Medium-Term Research and Development Plan (Ts-4). Margit Horváth (1979) conducted a survey in 1974 among the graduates of teaching, popular education and librarianship in Szombathely and Debrecen, 901 people answered the questionnaire. It found that there is a high fluctuation in the profession (65% of correspondence students had already changed jobs). Those who wanted to change expected higher social status and better conditions. Behind the change was a lack of autonomy, professional perspective and success, as well as the treatment by management. However, 80% of respondents would not change their profession.

Éva Benkő (1982), popular educator from Budapest, analysed the situation of 200 popular educators, their professional role perception and their opinion on the knowledge required for the profession. She found high turnover to be a characteristic feature of the profession, ranging from 23 to 45 percent in the 16 institutions surveyed. There were several reasons for the high fluctuation, but these did not change much compared to the Horváth study (e.g. job satisfaction, salary, or the coincidence of education and job title). In Benkő’s research, the interviewees referred to the lack of clarity of the professional requirements, the unevolved nature of the profession of popular educators, the rigidity of management and the lack of autonomy. Benkő divided the popular educators of the period into four groups, the acquiescents, the bustler-organizers, the enlighteners, and the catalysts (Benkő, 1982; Fónai, 2011: 237-238). The social situation of the popular educators was described by Nyilas (1984) on the basis of national data. His analysis is based on the factors that shape the status of occupational groups, namely education, income and prestige. In the 1980s, the proportion of people with only secondary school education (37.6%) and with no vocational qualification (55.3%) was very high among popular educators, while those who had an appropriate education were typically part-time (30-40% in Budapest, 60-80% in rural areas). In addition to their professionalism, this also affected the prestige of the popular educators. Incomes of popular educators were low compared to other intellectual occupations, and there were few opportunities to supplement them in the second, black and grey economy. Popular educators were typically first-generation intellectuals, half of them were the children of physical worker parents, a quarter of them of intellectual parents, and the proportion of teachers and council workers was high among intellectual parents. According to Nyilas, the qualification, the social composition, the debatable intellectual nature of the activity and the profitability of the people working in the field combine to create lower prestige, which in turn has an impact on income, the number of people choosing this career and contributes to a high proportion of “migrants”. In addition, the constructed nature of the occupation, its historical origins, its affinity with the teaching profession, and the ambiguity of competence boundaries, make it inherently less prestigious for intellectual groups (Nyilas, 1984: 44-45).

In the second half of the 1980s, Ilona Vercseg and András Földiák dealt with the issues of the image of a popular educator (Vercseg, 1988). This research focused primarily on professional role perceptions, and based on 108 interviews, nine distinctive role perceptions were identified. The research on the rural sample showed that 54.3 percent of the popular educators were first-generation intellectuals (in Budapest, the figure was half as high, 26.7 percent), i.e. the proportion of people from lower-status families among rural popular educators was high even in the 1980s, which means that the popular educator profession was typically a popular channel of intergenerational mobility, a break-out point for people of lower origin.

According to Vercseg’s role typology, the most common role interpretation was “to meet the current expectations of management” (Vercseg, 1988: 85). This means that the profession, which was assessed in many different ways in the eighties and nineties, typically responded to political expectations with a conformist attitude, but not as a “believer”. Two more distinctive sets of roles are highlighted: the role of communicating “everyday culture” (12.9% of respondents) and the role of “encouraging individual lifestyle”. This shows that the popular educators of the eighties had already gone beyond the different “enlightening” role of the popular educators of the fifties, sixties and seventies, and were open to everyday life and culture, and were hardly interested in transmitting “festive culture”.

The results of a research in Nyíregyháza in 1989 show that the accelerating processes of the regime change had only a minor impact on the opinions and expectations of the popular educators and the “lay people” (Fónai, 1990: 104-105). From the responses of the lay interviewees, two very definitive external career paths can be extracted. The external career profile is dominated by programme management (38.5%), furthermore, education (17%) and entertainment (6.6%). These features testify to the conventional image of the popular educator profession. The need for a popular educator who cares about people is barely present in this external career profile, and is more pronounced at the level of expectations. The conventional external career image had changed somewhat by the end of the 1980s, as the expectations and what was lacking in the work of the popular educators were: caring for the different strata and age groups (15.3%), and varied programmes that interested people (11.4%), which indicates the community-creating and community-building characteristics of the popular educators in the public’s needs. The population considers the versatility (44.7%) and “human” (12.5%) character of the knowledge of the popular educator to be decisive. Once again, an image of the profession as a whole, as public educators also value the versatility of their general knowledge (27.2%), their openness (8.9%) and their humanity (5.0%).

The rapidly changing profession in the 1990s can be seen in the research of Pál Diósi (Diósi, 1996, 1998). In many respects, the situation and trends we are already familiar with are reflected: 62% of professionals are women, four tenths work in one-person institutions and seven tenths belong to the professional middle generation, aged 31-50. Highlighting the interesting results, it appears that seven tenths of those working as popular educators started their careers as non-popular educators, yet 65% had no plans to change and 78% defined themselves as “popular educators”.

Conclusion

In relation to the popular educator profession, in other words occupation, career, vocation, professio (all five terms are used in the literature, although they do not have exactly the same meaning), we can highlight three characteristics: constructed, semi-professional, and deprofessionalised in a trendy way due to its rapid transformations. The popular educator profession is “constructed”, because in many periods, but especially in the 1950s and 1960s, the institutional system and expectations of the profession were formed earlier than it was organically formed (Nyilas, 1984; Fónai, 1990; Mankó, 1990). This top-down approach has contributed in many ways to the profession’s constant need for change – changes inspired partly by politics and partly by practice. This in itself does not mean that popular education has not become an occupation, a profession in the sociological sense of a profession (Parsons, 1968). It is clear that the knowledge needed for the profession has been outlined, transferred to higher educational institutions and the profession has created its own organisations. The definition of the knowledge required for the profession was the subject of ongoing professional debates between higher educational institutions and was influenced by politics, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, but also later. Constructedness, “inorganic” emergence, rapid, imposed changes have also contributed to the characteristic semi-professionalism of popular education (Etzioni, 1969; Kleisz, 2005). This character was reinforced by the high proportion of unqualified people in the popular educator profession (unthinkable for high status professions), the low prestige and low income of the profession, and the fact that the qualifications regulations did not differentiate between the different levels of qualification, so that a vocational college degree obtained at teacher training colleges was recognised as equivalent to a college or university degree. Popular education as a profession has always struggled to become a professio, but due to the nature of the activity and partly due to the nature of the training, it can be described more as a semi-profession. Constant, hectic changes in e.g. professional content and semi-professionalism deprofessionalized (Haug, 1973; Fónai, 2011) popular education, i.e. it broke the professional, political and “lay” consensus on professional knowledge and reduced the already low prestige of the profession.

Empirical popular educational research shows that at the end of the 1980s, the conventional professional roles and activity structure of popular educators still prevailed, but at the same time new, external, often “lay” expectations emerged, which meant turning to local societies and communities, meeting local social needs, and a kind of “market” behaviour prevailed, which further changed the traditional image and activity structure of popular educators.

A kutatási folyamatot és a tanulmány elkészítését a Nemzeti Művelődési Intézet Közművelődési Tudományos Kutatási Program Kutatócsoportok számára alprogramja támogatta.

Literature used

- Benkő, É. (1982). Megszállottak, átutazók, beletörődők. Népművelők Budapesten. Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda.

- Boros, L. (2017). A nyolcvanas évek ifjúsági mozgalmai. Educatio, 26(1), 3–14.

- Diósi, P. (1996). Szabad csapatok? Budapest: Budapesti Népművelők Egyesülete, Német Népfőiskolai Szövetség.

- Diósi, P. (1998). Ex Lex ’97 (Népművelők magukról, foglalkozásukról és távlataikról). Budapest: Német Népfőiskolai Szövetség.

- Drabancz, M. R. (2008). Az értelem keresése vagy ilyen volt Tariménes iskolája. In A tudásteremtő fakultás eredményei (pp. 37–47). Nyíregyháza: Nyíregyházi Főiskola GTK.

- Drabancz, M. R., & Fónai, M. (2005). A magyar kultúrpolitika története 1920–1990. Debrecen: Csokonai Kiadó.

- Etzioni, A. (Ed.). (1969). The semi-professions and their organization. New York: The Free Press / Macmillan.

- Fónai, M. (1986). Pályakép – és ami mögötte van. Szabolcs–Szatmári Szemle, 21(3), 348–353.

- Fónai, M. (1988). Az értelmiség modell-szerepéről egy kistelepülésen. Kultúra és Közösség, 15(2), 95–111.

- Fónai, M. (1989). Értelmiségiek és aspirációk. Pedagógiai Műhely, 15(12), 44–51.

- Fónai, M. (1990a). Pályatükör: Számokban a népművelőkről. In M. Mankó (Szerk.), Nevelés- és Művelődéstudományi Közlemények (pp. 103–110). Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei György Kiadó.

- Fónai, M. (1990b). Főiskolai hallgatók értelmiségképe. In S. Frisnyák (Szerk.), Nyíregyházi Főiskola Tudományos Közleményei: Társadalomtudományi Közlemények, 12/F. Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei György Kiadó.

- Fónai, M. (1991). Egy konstruált szakma: Számokban a „népművelésről”. In M. Fónai (Szerk.), Népnevelőtől a kulturális menedzserig (pp. 3–9). Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei Kiadó és Nyomda.

- Fónai, M. (1992). Egy értelmiségkutatás lehetséges keretei. In I. Udvari (Szerk.), Nyíregyházi Főiskolai Tanulmányok I. (pp. 199–214). Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei György Könyvkiadó.

- Fónai, M. (1994). Értelmiség és elit. Dimenziók, 2(2), 1–12.

- Fónai, M. (1997). Értelmiség, értelmiségi funkciók és szerepek [Kandidátusi disszertáció, Magyar Tudományos Akadémia]. MTA Kézirattár.

- Fónai, M. (2008). Az értelmiségkép változásai a poszt-szocialista átmenet publicisztikájában [Kézirat].

- Fónai, M. (2011). Művelődésszervezők és andragógusok a DPR kutatásokban. In G. Erdei (Szerk.), Andragógia és közművelődés. Régi és új kihívások előtt a közművelődés új évtizedében (pp. 232–254). Debrecen: Debreceni Egyetem.

- Fónai, M., & Drabancz, M. R. (2000–2001). Vázlat a népművelő és a művelődésszervező képzés történetéhez Nyíregyházán. Kultúra és Közösség, 5(IV–I), 155–165.

- Haug, M. R. (1973). Deprofessionalization: An alternative hypothesis for the future. In P. Halmos (Ed.), Professionalization and social change (Sociological Review Monograph No. 20). University of Keele.

- K. Horváth, Zs. (2010). A gyűlölet múzeuma. Spions, 1977–1978. Korall, 39, 5–30.

- Horváth, M. (1979). Népművelő-könyvtárosok a pályán. Budapest: Népművelési Propaganda Iroda.

- Im Hof, U. (1995). A felvilágosodás Európája (pp. 94–99). Budapest: Atlantisz Kiadó.

- Kristóf, L. (2011). Elitkutatások Magyarországon 1989–2010. In I. Kovách (Szerk.), Elitek a válság korában. Magyarországi elitek, kisebbségi magyar elitek (pp. 37–56). Budapest: Argumentum – MTA PTI.

- Kristóf, L. (2014). Véleményformálók. Hírnév és tekintély az értelmiségi elitben. Budapest: MTA TK – L’Harmattan.

- Koncz, G. (2002). Művelődési otthonok: Komplex elemzés, 1945–1985. Szín, 7(1–2), 15–54.

- Mankó, M. (1990). A népművelés funkcióváltozásai. In M. Mankó (Szerk.), Nevelés- és Művelődéstudományi Közlemények (pp. 89–102). Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei György Kiadó.

- Mankó, M. (1991). Megújítási törekvések egy régi–új szakterületen. In M. Fónai (Szerk.), „Népnevelőtől” a kulturális menedzserig (pp. 29–52). Nyíregyháza: Bessenyei Kiadó és Nyomda.

- Nyilas, Gy. (1984). A népművelők társadalmi helyzete. Palócföld, 18(3), 40–46.

- Parsons, T. (1968). Professions. In International encyclopedia of social sciences (Vol. 12, pp. 536–547).

- Ponyi, L., Arapovics, M., & Bódog, A. (Szerk.). (2019). Magyarországi múzeumok, könyvtárak és közművelődési intézmények reprezentatív felmérése. Budapest: Szabadtéri Néprajzi Múzeum – Múzeumi Oktatási és Módszertani Központ – NMI Művelődési Intézet Nonprofit Közhasznú Kft. – Országos Széchényi Könyvtár Könyvtári Intézet.

- Ponyi, L. (2023). Folyamatosság és megszakítottság a közösségi művelődés történeti dimenzióiban. Kulturális Szemle, 10(2), 119–130.

- Seton-Watson, H. (1970). Az értelmiségiekről. Történelmi Szemle, 13(4), 517–528.

- Szalai, E. (1996). Az elitek átváltozása. Tanulmányok és publicisztikai írások 1994–1996. Budapest: Cserépfalvi Kiadó.

- T. Kiss, T. (2000). A népnevelőtől a kulturális menedzserig. Fejezetek a népművelőképzés fejlődéstörténetéből. Budapest: Új Mandátum Könyvkiadó.

- T. Kiss, T., & Tibori, T. (2015). Az önépítés útjai. Durkó Mátyás munkássága. Szeged: Belvedere Meridionale.

- T. Molnár, G. (2016). A népművelőtől a közösségszervezőig – A kultúraközvetítő szakemberképzés negyven éve Szegeden. In E. Juhász (Szerk.), A népműveléstől a közösségi művelődésig (pp. 143–153). Debrecen: Debreceni Egyetem.

- Vercseg, I. (1988). Szocializáció, szerep, érték a népművelői pályán. Budapest: Múzsák Közművelődési Kiadó.

-